Operation Endgame: Deconstructing Venom RAT’s Infrastructure, Identities, and Financial Trails

The latest phase of Operation Endgame, carried out in November 2025, represented one of the most sweeping crackdowns on cybercrime infrastructure in recent years. With over a thousand servers disrupted and multiple darkweb services seized, the operation targeted several malware ecosystems that had quietly powered credential theft, remote access, and automated cyber-offences on a global scale.

At the centre of this coordinated action were three major enablers of cybercrime: the Rhadamanthys infostealer, the VenomRAT remote access trojan, and the Elysium botnet. Authorities confirmed that the primary suspect behind VenomRAT was arrested in Greece on 3 November 2025, highlighting the operation’s reach not only across networks but also across individuals operating them.

While our previous report dissected the Rhadamanthys ecosystem in depth, this investigation shifts the focus to VenomRAT, a tool whose commercial presence and decentralised distribution have helped it remain deeply embedded in the malware-as-a-service landscape. Operation Endgame has created a rare opportunity to unpack the networks surrounding VenomRAT: its public storefronts, hidden Tor services, Telegram channels, reseller activity, impersonation attempts, and leaked data artifacts.

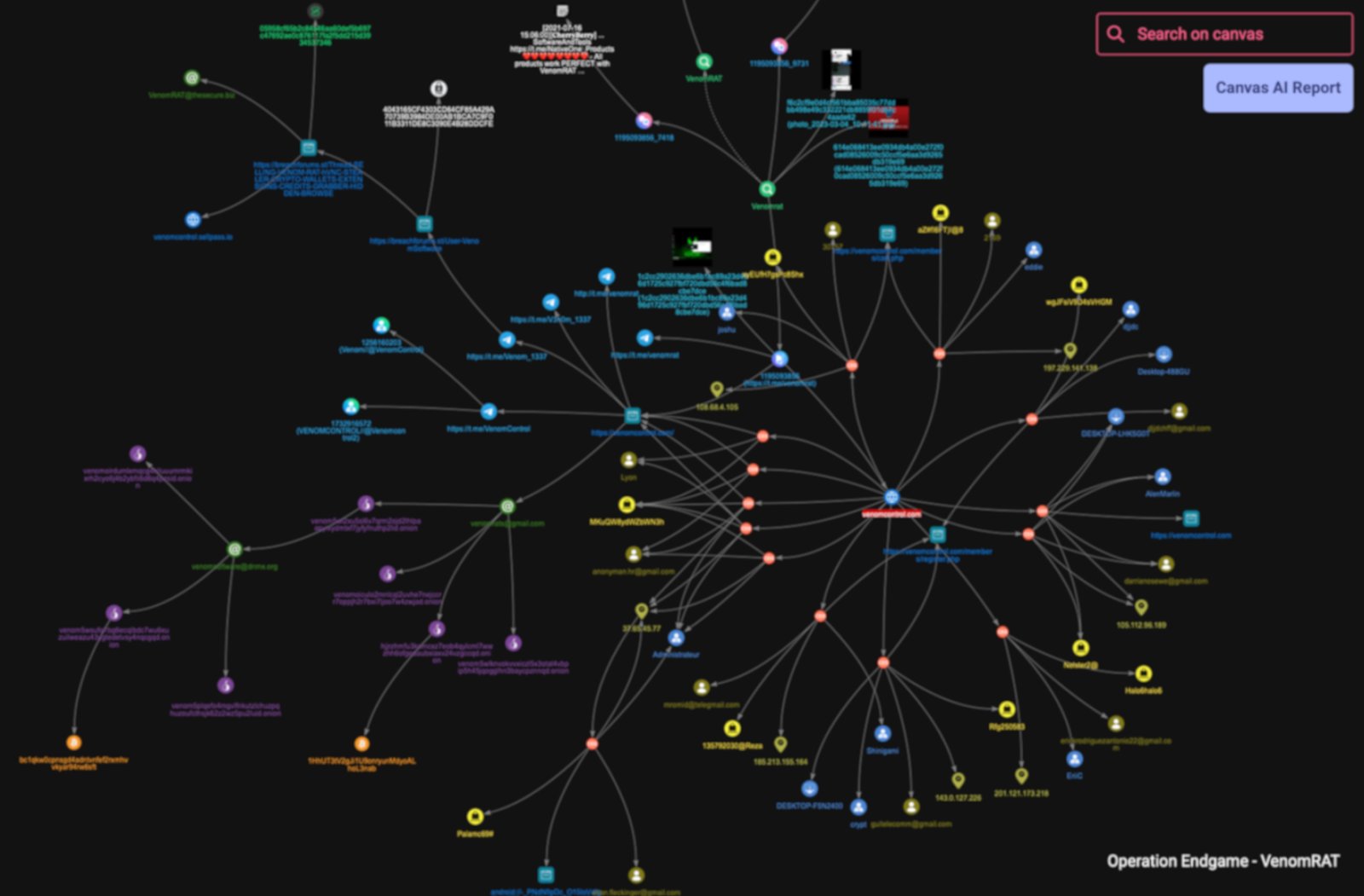

What started as a simple domain check quickly escalated into a layered ecosystem involving Telegram networks, Tor-hosted services, possible cryptocurrency activity, underground forum identities, impersonation attempts, and traces of leaked credentials tied to Venom’s infrastructure. Rather than summarising these elements upfront, this report walks through them step by step: showing how each discovery leads to the next, and how VenomRAT’s operational footprint expands far beyond its public storefronts.

Background & Context

Before Operation Endgame placed it squarely in the spotlight, VenomRAT had already spent several years circulating quietly through criminal marketplaces, Telegram groups, and small developer communities. Marketed as a multifunctional Remote Access Trojan bundled with hVNC and credential-stealing capabilities, it occupied a familiar but influential space in the malware-as-a-service ecosystem: inexpensive enough for entry-level actors, flexible enough for experienced operators, and heavily promoted across platforms that value anonymity and speed over stability or security.

Unlike more mature stealer families with large affiliate programs, VenomRAT thrived through direct sales, private customer channels, and an ever-expanding web of unofficial resellers and impersonators. Its operators routinely maintained both clearnet storefronts and Tor-hosted mirrors, a strategy that made the service accessible to low-skill buyers while keeping parts of its ecosystem insulated from takedowns. Over time, VenomRAT became a common component in low- to mid-tier intrusion chains, particularly those relying on phishing attachments, cracked software installers, and spam-delivered loaders.

Publicly, the tool did not draw the same attention as larger botnets or high-volume stealers. Behind the scenes, however, it maintained a steady presence in incident reports, malware sandboxes, and underground discussions, enough to position it as a persistent nuisance to defenders and a reliable utility for threat actors. This relative obscurity began to change once Operation Endgame identified VenomRAT as one of the three primary malware ecosystems enabling large-scale compromise activity. The arrest of the suspected operator in Greece on 3 November 2025 marked the first public disruption tied directly to VenomRAT, creating a rare window to examine its infrastructure during a moment of instability.

This investigation builds on that moment. What initially appeared as a straightforward case rapidly expanded into a broader view of VenomRAT’s operational environment, its distribution networks, and the traces left behind by both its users and its developer.

Incident Trigger & Initial Investigation

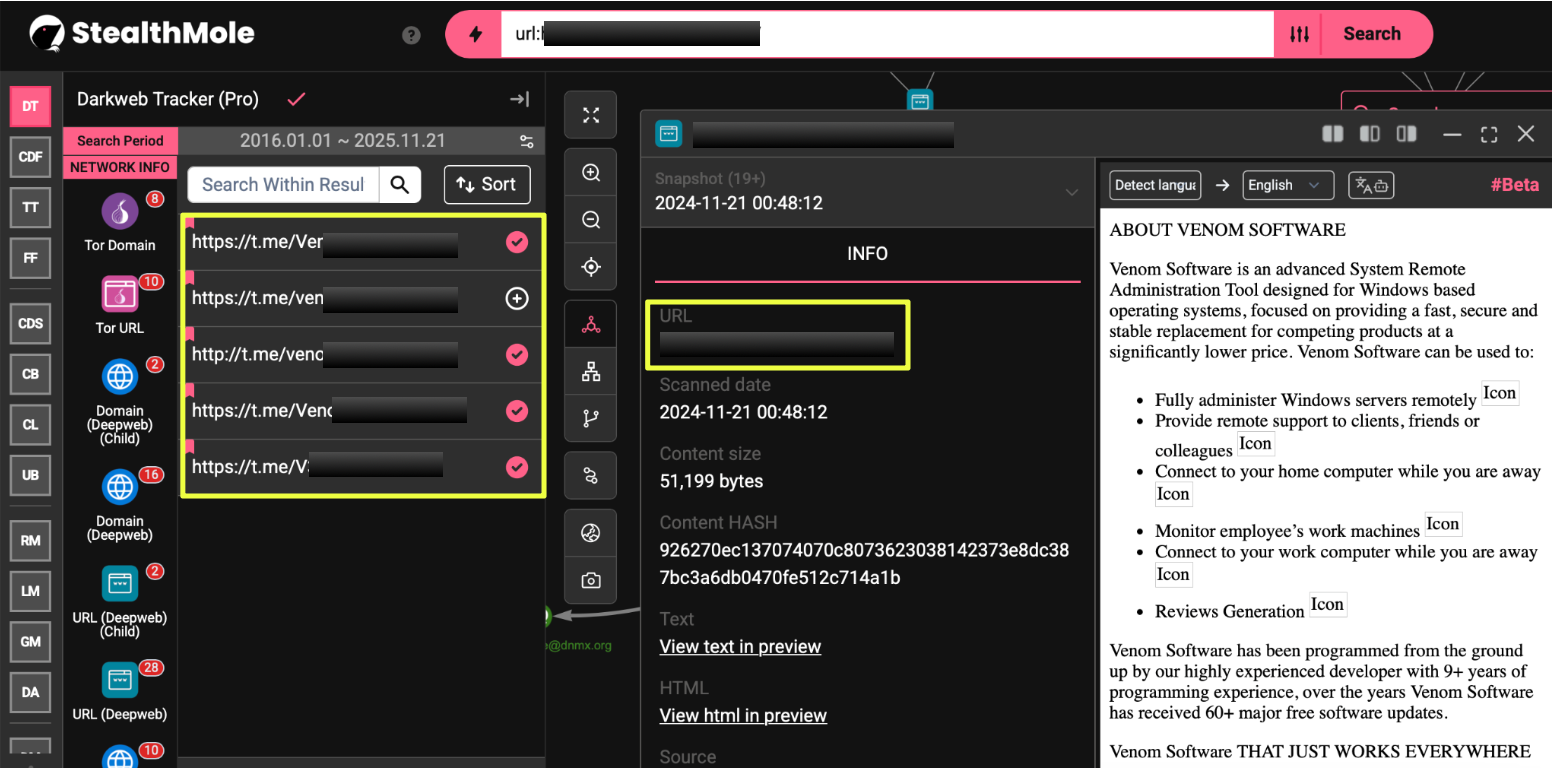

The VenomRAT investigation began with a simple exploratory query on StealthMole’s Darkweb Tracker. Since VenomRAT was one of the three malware ecosystems disrupted during Operation Endgame, the initial goal was only to check whether its name still appeared across darkweb chatter following the takedowns. For this purpose, the term “VenomRAT” was run through the tracker without any prior assumptions about active infrastructure or associated actors.

This seemingly small query immediately returned an unexpected lead: a Telegram-sourced image showing an automated bot notification referencing a “Venom RAT” infection event. The message included system details from a compromised machine and displayed the label “CODED BY MR SAMI”, suggesting an active or recently active community around the malware. Alongside the screenshot, the dataset also surfaced a QR-code-branded malware image linked to a file named venomrat-malware.png, complete with associated hashes. Although the QR code could not be decoded from the available sample, its presence indicated that VenomRAT-related files were circulating in underground channels.

These two artifacts, the Telegram bot screenshot and the malware image, formed the first concrete signs that VenomRAT activity extended beyond what was publicly known from Operation Endgame. With no domain, operator identity, or infrastructure yet established, the next step in the investigation was straightforward: pivot from the keyword “VenomRAT” into StealthMole’s Telegram Tracker to determine whether any groups, handles, or communities consistently referenced the tool.

Mapping the Venom Ecosystem

The early indicators from StealthMole’s darkweb search suggested that VenomRAT had not fully disappeared despite Operation Endgame. To understand the scope of what remained active, the investigation moved from isolated artifacts to the broader ecosystem that might surround them. The first step was to identify whether VenomRAT maintained any clear, public-facing presence: a storefront, a support page, or even a branded communication hub that could act as an anchor point for the rest of the analysis.

Public-Facing Infrastructure

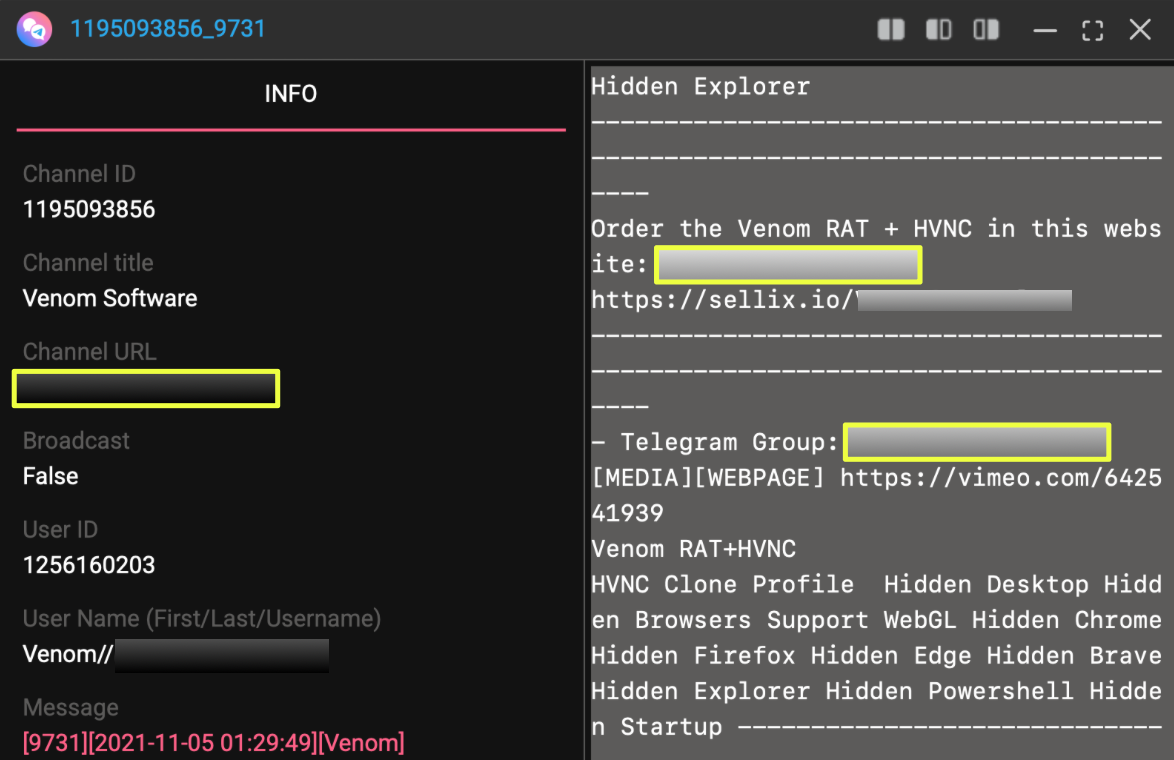

The pivot began with StealthMole’s Telegram Tracker, using the same keyword that surfaced the initial darkweb artifacts: “VenomRAT.” This search returned several Telegram posts in which VenomRAT was explicitly mentioned, but one stood out immediately. Multiple messages referenced an “official group” under the name Venom Software, consistently directing users to the channel https://t.me/ve*******t. The content inside these references included product announcements, screenshots of the RAT’s interface, promotional videos hosted on Vimeo, and contact details for a private support account, @Ve********l.

Crucially, these messages repeatedly pointed toward a single external domain, https://ve*********l.com/, claiming it as the official website for purchasing and managing VenomRAT builds. At this stage of the investigation, nothing confirmed whether the site was genuinely controlled by the operator or part of the larger network of impersonators often seen around popular malware families. Nonetheless, the repeated cross-linking across Telegram posts made it a clear next point of focus.

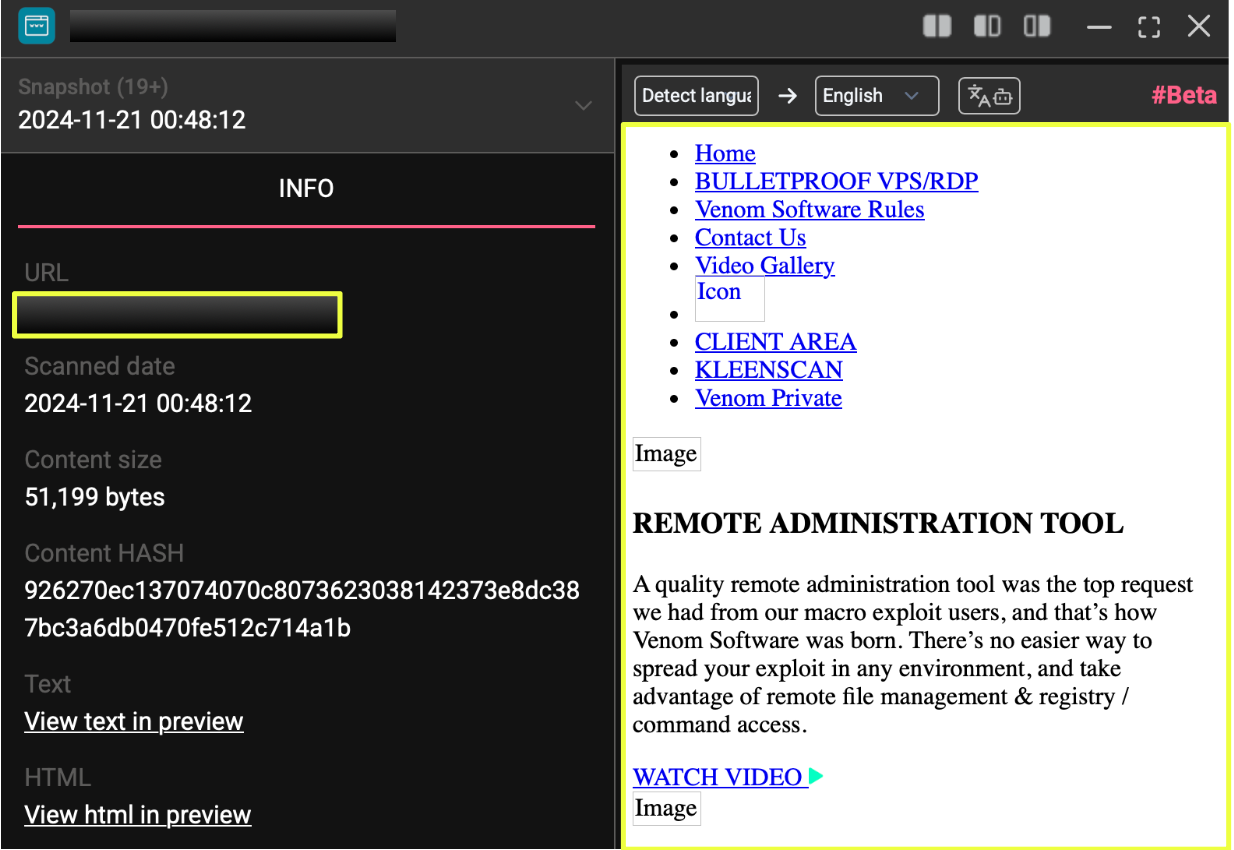

Visiting the domain revealed a fully developed website marketed under the name Venom Software, with product pages, feature descriptions, pricing tiers, a client login area, and promotional material describing various versions of VenomRAT and its hVNC extensions. The presence of structured navigation, order pages, and live content suggested that this was not a defunct asset, it was an operational platform. The site also linked out to a commercial storefront at https://ve******l.sellpass.io/, reinforcing the impression that this ecosystem sought legitimacy within the underground market by maintaining multiple redundant purchase channels.

This was the first indication that VenomRAT operated through a hybrid model: a clearnet-facing presence designed to attract buyers, paired with a Telegram community that acted as its recruitment and support layer. From this point, the investigation expanded into deeper, less visible parts of the infrastructure to determine how the public-facing elements connected to VenomRAT’s broader ecosystem.

Expansion Into Hidden & Underground Spaces

While VenomRAT’s clearnet-facing website and Telegram presence suggested an active commercial operation, those elements alone rarely represent the full footprint of a malware service. Most mature MaaS ecosystems maintain layers of redundancy: hidden services, mirrors, alternative stores, and secondary communication channels, to ensure continuity if any single platform is disrupted. With this in mind, the investigation expanded beyond the surface-level infrastructure to determine whether VenomRAT maintained deeper operational anchors that were not immediately visible from its public channels.

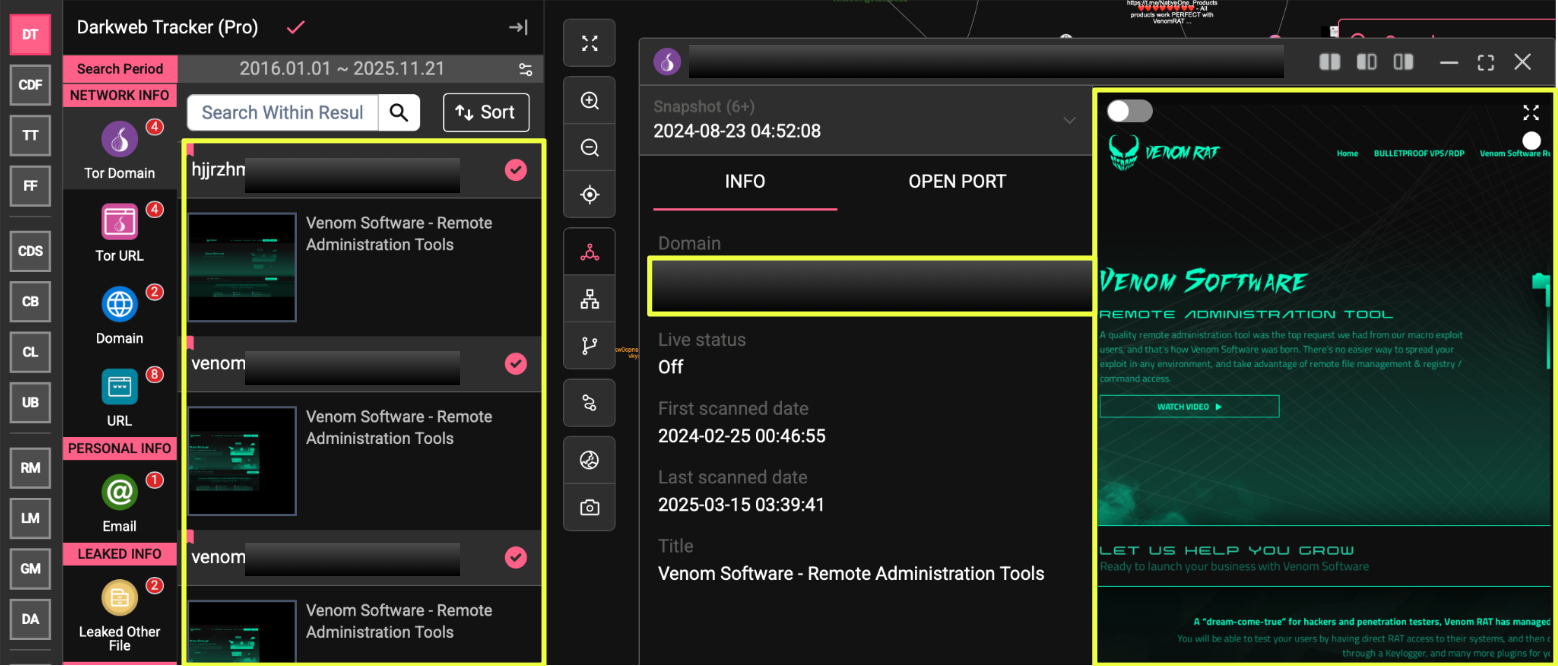

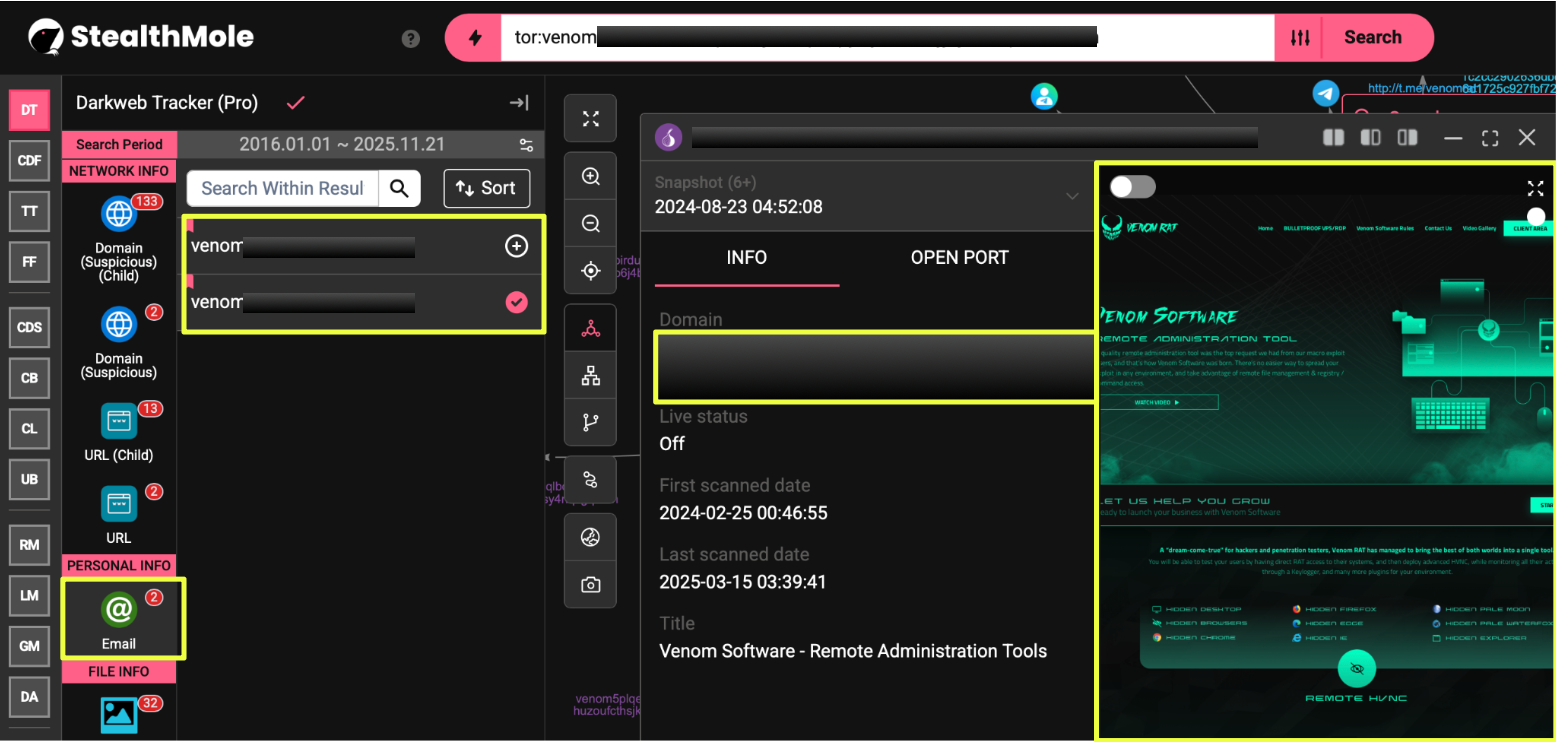

The first signs of this emerged when StealthMole’s Darkweb Tracker was used to pivot from the website ve*******l.com. Rather than returning unconnected chatter or generic references, the tracker surfaced multiple Tor-hosted domains carrying the Venom naming pattern. These included long-form .onion addresses configured with “venom” prefixes, each appearing to host material linked to the same brand identity seen on the clearnet site. The discovery of several such mirrors suggested that the Venom ecosystem was deliberately distributed across different layers of the internet.

- Venom************************************************lid.onion

- Venom************************************************jad.onion

- Hjjrz************************************************cqd.onion

- Venom************************************************nqd.onion

- Venom************************************************sid.onion

- Venom************************************************gqd.onion

- Venom************************************************uid.onion

In addition to hidden services, the darkweb results also pointed to an expanded set of contact identifiers associated with VenomRAT. Among them was an additional operational email, ven********e@dnmx.org, found embedded within one of the Tor snapshots. This was notable because it did not appear anywhere on the clearnet site or in the Telegram messages observed earlier. Its presence on a hidden service implied that Venom’s operators were maintaining separate communication channels depending on where buyers entered the ecosystem.

More importantly, the structure of these hidden services and the consistency of their naming indicated intentional mirroring rather than opportunistic impersonation. Each one reflected the same brand elements observed on the main domain: Venom logo variations, product descriptions, and long-form feature lists. Together, these early findings revealed that VenomRAT was operating on multiple fronts simultaneously, with its clearnet, Telegram, and Tor presences reinforcing one another rather than functioning as isolated assets.

Tracing the Operator Behind the Brand

The transition from infrastructure to identity began within the same Telegram messages that pointed to VenomRAT’s public website. Among the promotional posts and feature announcements circulating inside https://t.me/ve******t, several messages encouraged buyers to verify authenticity by contacting the operator directly. The preferred contact handle, @Ve******l, appeared repeatedly, both in public posts and in automated bot messages that accompanied screenshots of infected systems. This handle quickly became the first stable reference point for mapping the human side of the operation.

As the investigation expanded, StealthMole’s dataset surfaced additional Telegram usernames tied to the same ecosystem. Variations such as @Ve***m_1***7 and the group https://t.me/V****m_1****7 appeared in separate fragments of underground chatter, often used in contexts where VenomRAT was being promoted, resold, or discussed by users seeking support. These parallel references hinted at a larger identity cluster rather than a single isolated account, suggesting that VenomRAT’s operator maintained multiple fronts or that impersonation was common enough to necessitate alternative contacts.

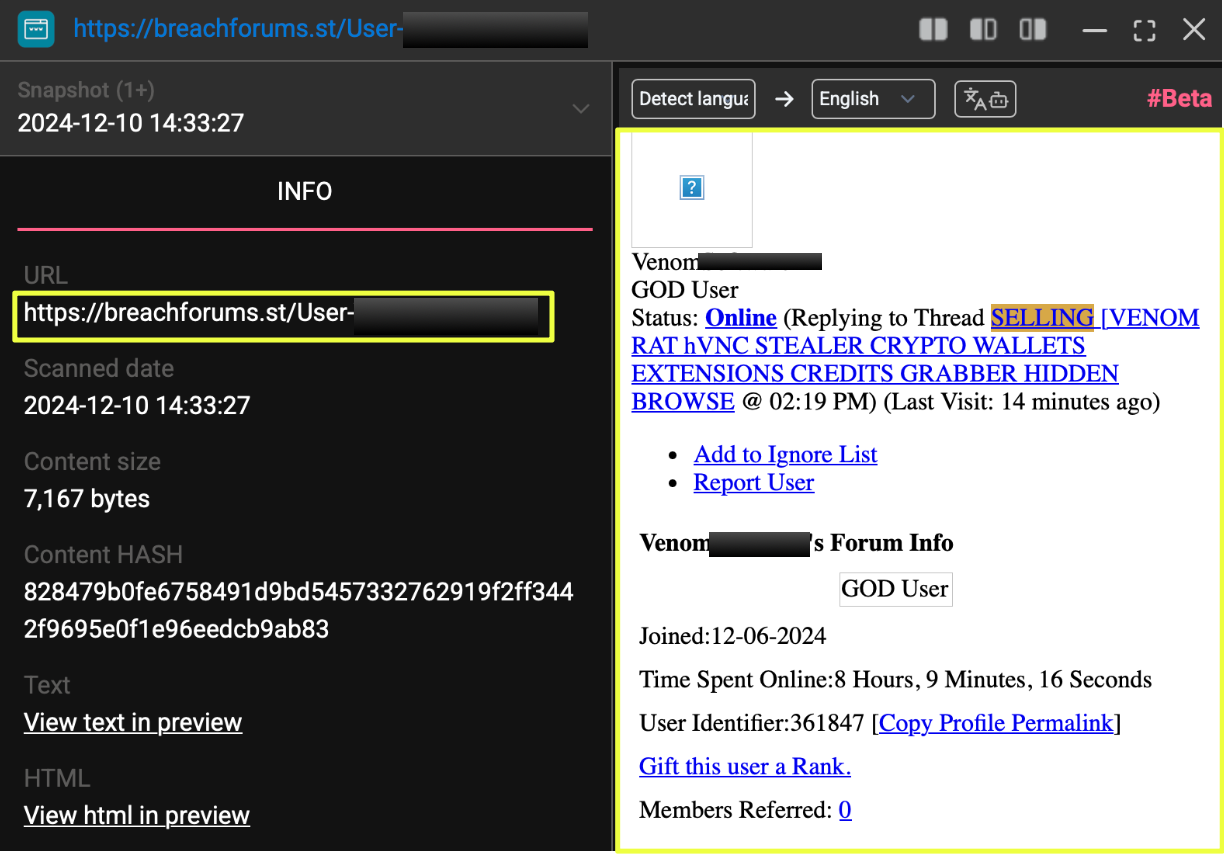

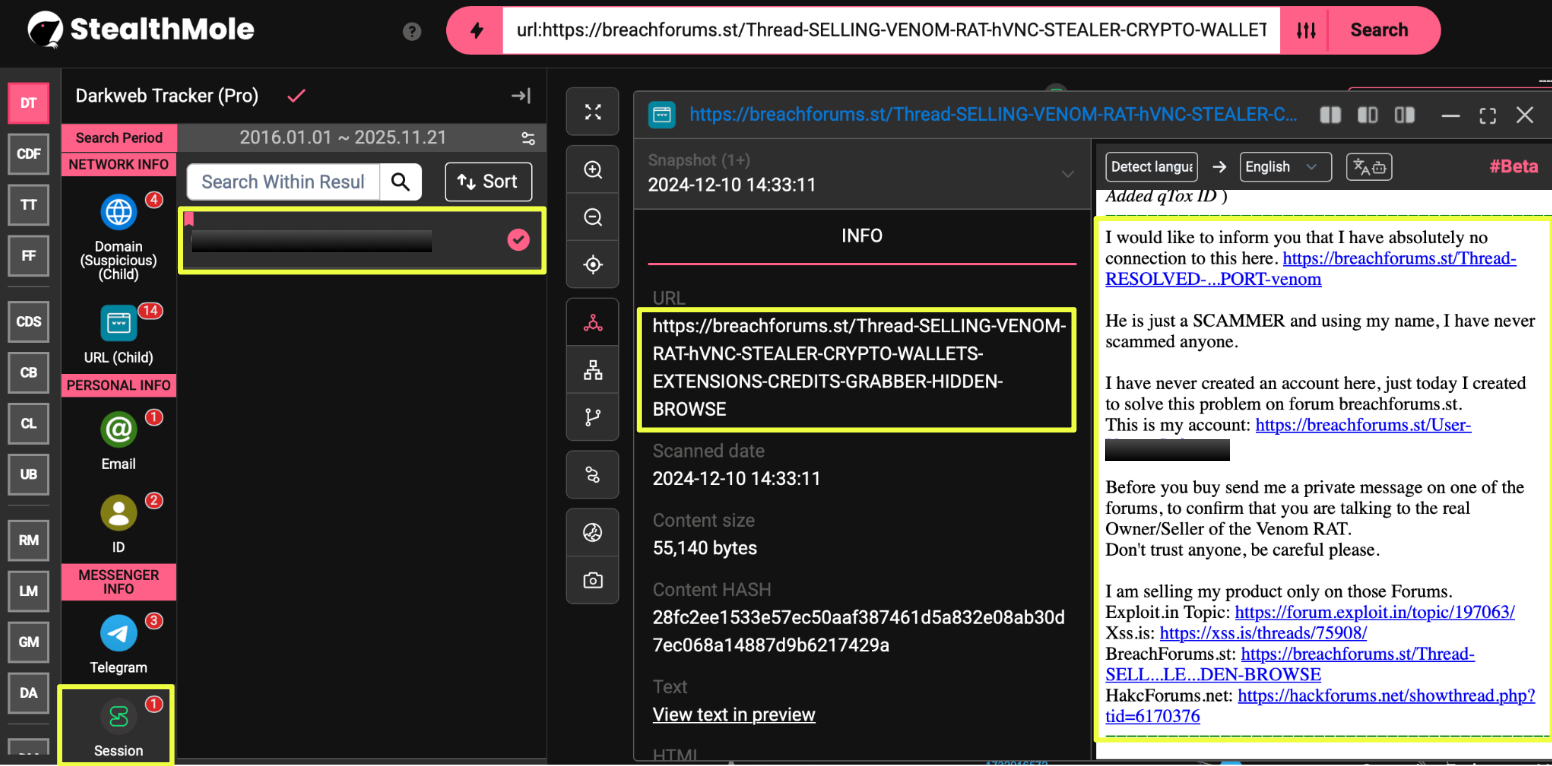

To validate which of these profiles were legitimate, the investigation followed the references outside Telegram and into underground forums. This pivot led directly to a profile on BreachForums, registered under the name Venom*****e. The account’s activity aligned closely with the ecosystem already uncovered: product updates matching those posted on Telegram, consistent branding, and marketing language identical to what appeared on the clearnet site and Tor mirrors.

- https://breachforums.st/User-Venom*******e

What stood out most was a dedicated sales thread attributed to the same profile, promoting the exact combination of features advertised elsewhere: VenomRAT, hVNC, credential harvesting, browser extensions, and crypto wallet theft. The thread also offered a set of contact options that mirrored the Telegram findings, confirming that the same actor operated across both platforms. This thread represented the first verifiable bridge between VenomRAT’s surface presence and its underground operator, forming a clear pathway for the next stage of the investigation.

With an operator identity now emerging, the focus shifted toward understanding the broader environment surrounding the service, not only who was selling it, but how it was being used, who interacted with it, and what internal weaknesses existed within its infrastructure.

Internal Exposure: Early Signs of Compromised Accounts

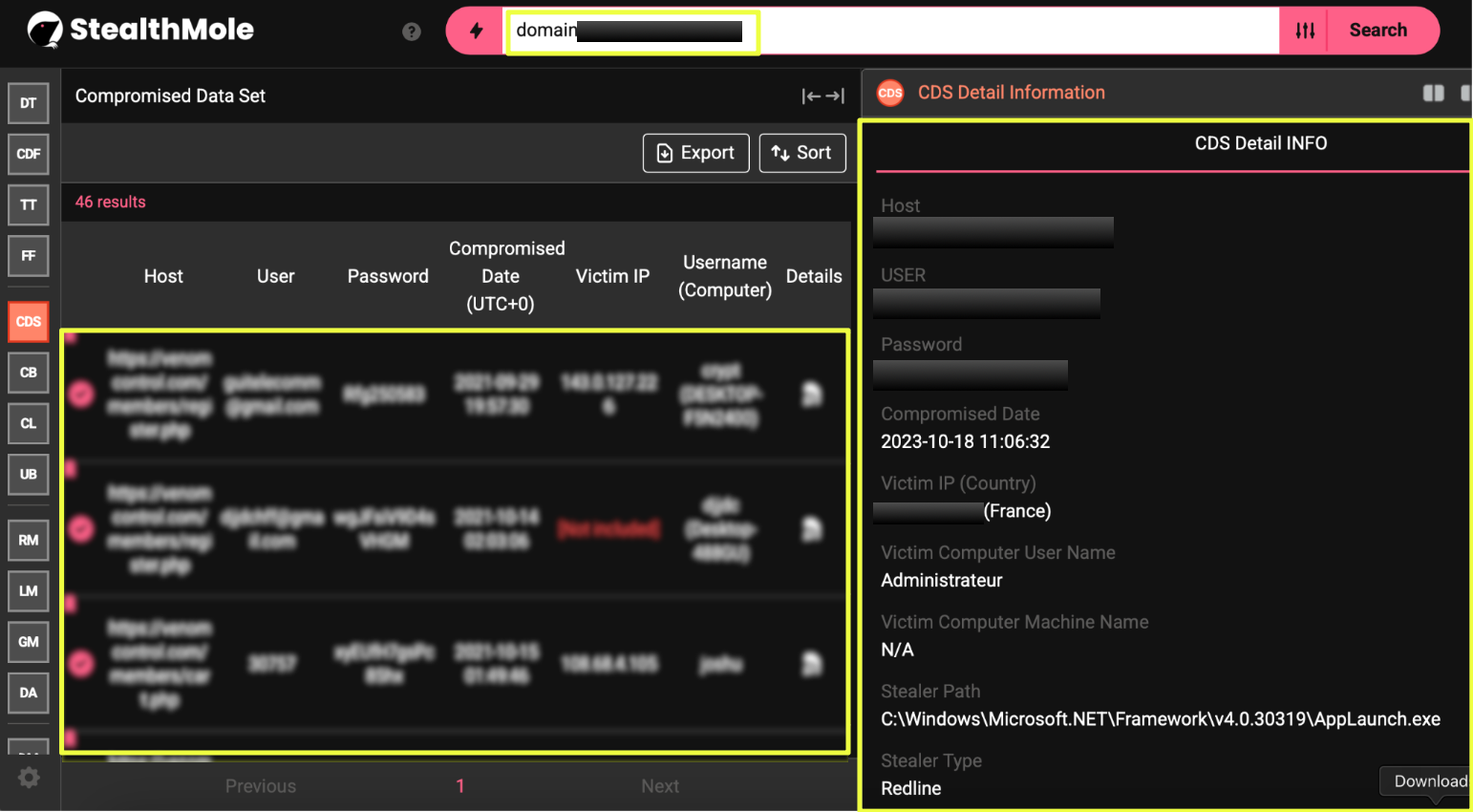

Once the VenomRAT operator’s presence across Telegram and BreachForums had been established, the investigation turned back to the infrastructure supporting the service, particularly the domain venom******l.com, which functioned as the central hub for sales, authentication, and customer access. Given the volume of underground activity surrounding VenomRAT, the domain became an obvious candidate for a credentials check to determine whether any associated accounts had surfaced in stealer logs or breached databases.

Running venom*******l.com through StealthMole’s Compromised Data Set immediately revealed that the ecosystem was not only active but internally exposed. The domain returned a significant number of leaked account entries tied to users who had interacted with the venom*******l platform, some appearing to be ordinary customers, others showing signs of elevated privileges such as administrative panel access. Even at this early stage, the sheer quantity of compromised entries suggested that VenomRAT’s user base was repeatedly infected by commodity stealers while interacting with the platform.

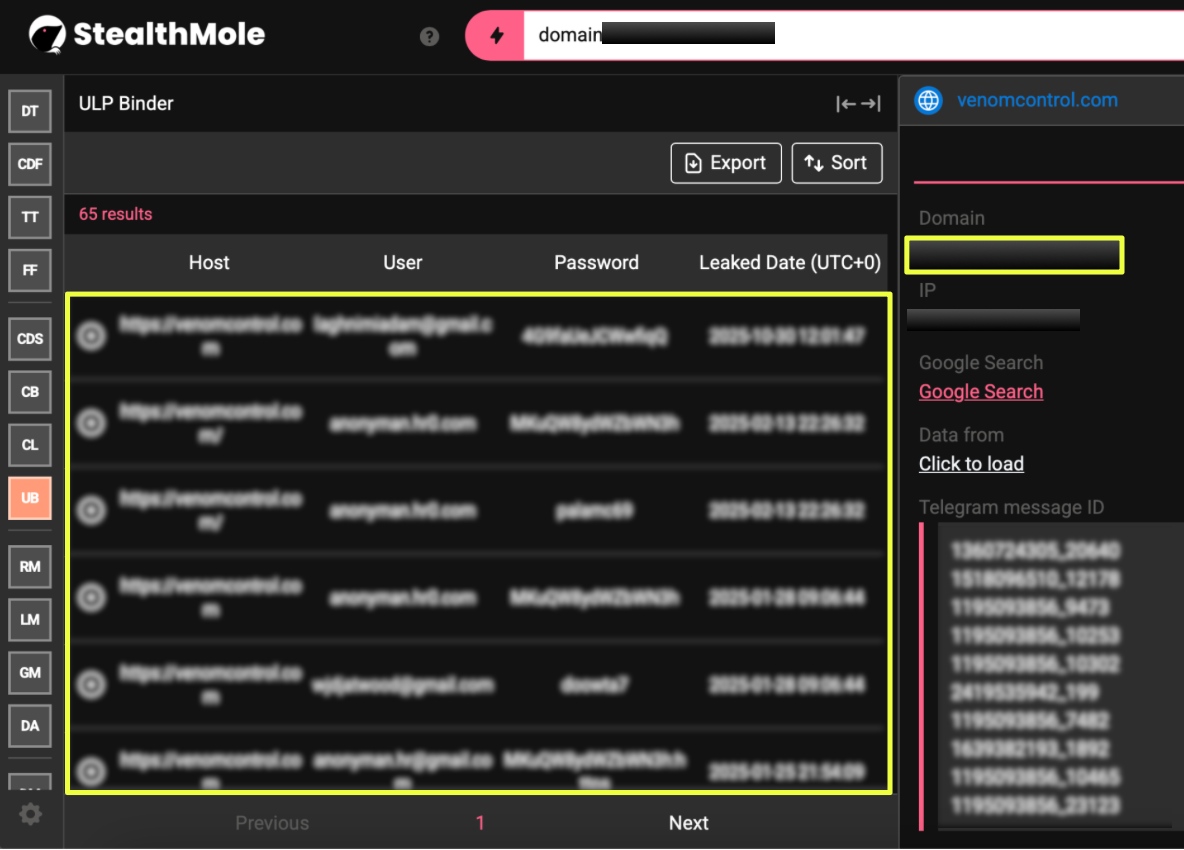

This pattern deepened further when the domain was pivoted through StealthMole’s ULP Binder, which surfaced an even broader set of exposed credentials linked to the same infrastructure. These results indicated that VenomRAT’s ecosystem was not insulated from the threats it helped propagate; in fact, many of its own operators and buyers appeared to be victims of credential theft themselves. Although the full scope of these leaks is detailed later in the report, these initial findings marked a turning point, shifting the investigation from simple infrastructure mapping to understanding how VenomRAT’s internal user environment had been repeatedly compromised over time.

The combination of exposed accounts, privileged users appearing in stealer logs, and repeated password reuse created a clearer picture of an ecosystem operating without meaningful OPSEC safeguards. With these cracks emerging in the internal infrastructure, the next phase of the investigation examined what the exposed data could reveal about the operational footprint of VenomRAT and how these compromises connected back to its wider network.

Internal Exposure: Administrator Accounts and Operational Weaknesses

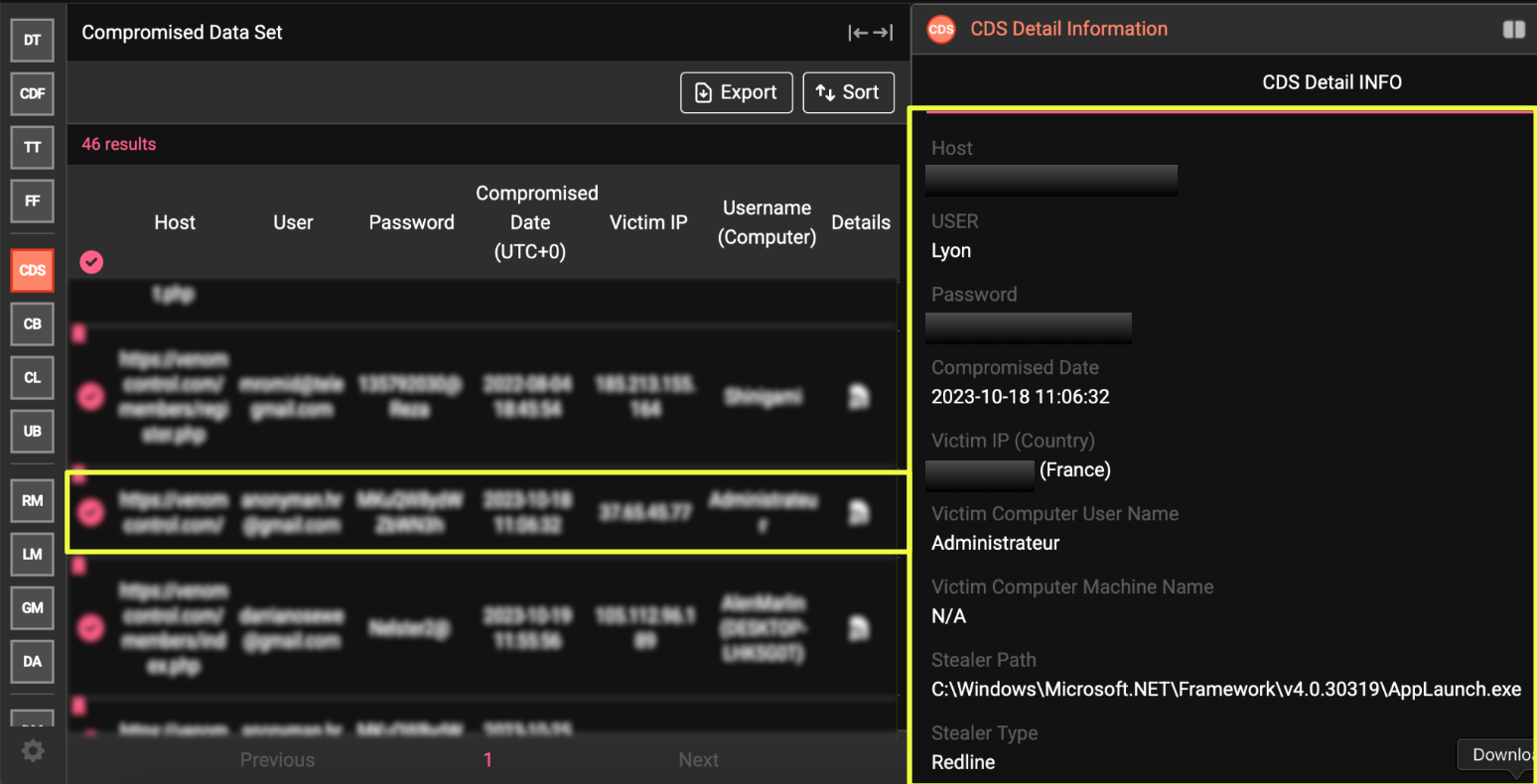

The compromised-credential results tied to venom*******l.com quickly revealed that the weaknesses in the VenomRAT ecosystem were not limited to its customers. A closer look showed that at least one individual appearing to hold administrator-level access to the venom*******l platform had themselves been repeatedly compromised by commodity stealers.

The earliest and most telling entry surfaced through StealthMole’s datasets was an account labeled “Lyon.” This user appeared inside logs associated with backend pages such as /members/index.php and /members/register.php, strongly suggesting an elevated role within the venom*******l system. What made Lyon’s presence especially revealing was the metadata tied to the account. The logs showed activity originating from a French IP address: 3*.*5.*5.*7. The captured environment looked like a personal workstation, not a dedicated administrative machine, and the browser-based credentials were exfiltrated through RedLine stealer infections.

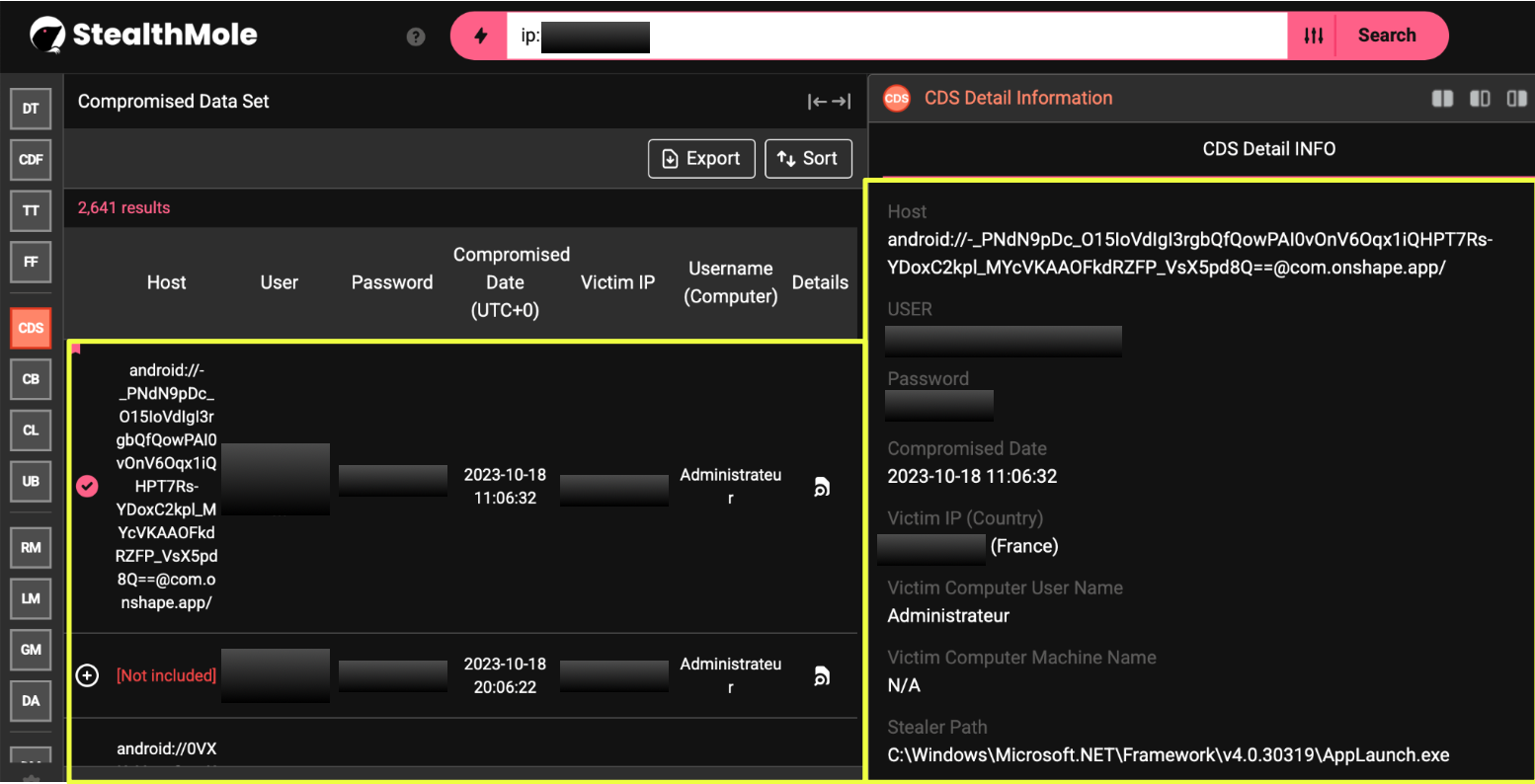

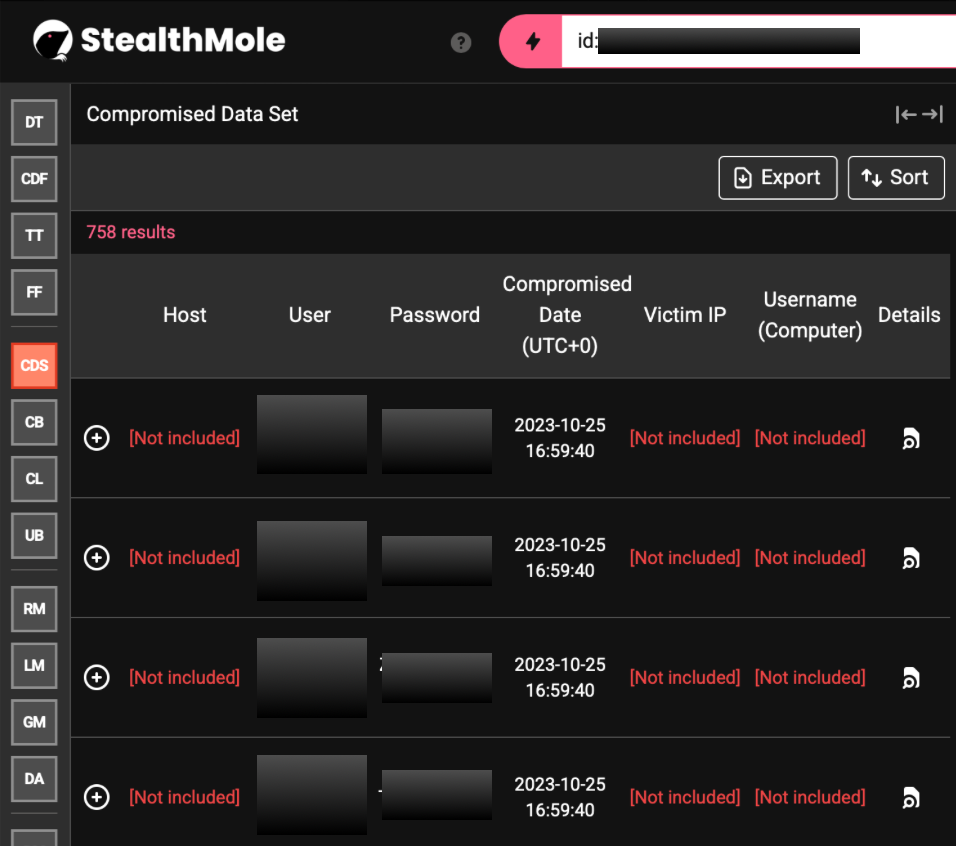

Further investigation into the same IP address expanded the picture. Multiple identifiers were associated with the device, including the email el****n.fl******r@gmail.com. When this email was run through StealthMole’s Compromised Data Set, it returned 758 leaked entries, spanning numerous stealer infections over time. The sheer volume of exposures linked to this email suggested that the machine behind IP 3*.*5.*5.*7 had been compromised repeatedly across several years.

This French IP was not the only trace tied to the operator cluster. Additional entries connected to venom*******l’s domain surfaced the email addresses anon*****n.hr@gmail.com and anon******.hr0.com, both appearing in leaked credential sets with the same repeatedly reused password. These accounts were not one-off victims; they showed persistent patterns of exposure across both CDS and ULP Binder results, a sign that their owners were accessing venom*******l via infected browsers and doing so regularly enough to leave a repeated footprint.

These findings exposed a recurring theme: the VenomRAT ecosystem was not only externally distributed across Telegram, hidden services, and clearnet storefronts, but internally compromised by the very malware families circulating in the underground scene. The presence of administrator credentials, including Lyon’s, in multiple leaks provided rare visibility into the operational side of the service and raised deeper questions about how these internal weaknesses shaped the broader VenomRAT network.

Ecosystem Behaviour and Victim Indicators

The operational weaknesses uncovered within VenomRAT’s administrative accounts provided an unusual vantage point into the broader ecosystem surrounding the malware. Because many of the leaked credentials came from stealer infections, RedLine being the most common, the exfiltrated logs often contained screenshots, system metadata, browser artefacts, and files harvested from both the operator and their customers. These artefacts made it possible to observe, indirectly, the types of environments interacting with VenomRAT and the behaviours of the individuals deploying it.

One recurring pattern was the presence of VenomRAT-related tooling on machines belonging to ordinary users rather than hardened threat actors. Several leaked logs showed personal desktops running RAT builders, cracked malware toolkits, or combinations of multiple remote access tools. These machines frequently had insecure configurations, stored browser passwords, and unpatched software, all factors that made them easy targets for competing stealers. In multiple cases, filenames and directory paths referenced other malware such as AsyncRAT and crypters, suggesting that a portion of VenomRAT’s customer base were entry-level operators experimenting with various tools simultaneously.

Within the administrative leaks, similar behaviours appeared. The French machine linked to IP 3*.*5.*5.*7 not only contained operational credentials but also stored browser-driven logins and auto-fill entries, the same weaknesses commonly observed in customer-side infections. The leaked data tied to el****n.fl******r@gmail.com, with its 758 stealer results, reflected repeated exposure to infection chains typical of low-sophistication actors, a surprising finding given this account’s proximity to VenomRAT’s backend systems.

Overall, these indicators showed an ecosystem with minimal internal hygiene, blurred roles between operators and customers, and a victim base shaped by opportunistic deployment rather than coordinated campaigns. This behavioural profile became essential when reconstructing VenomRAT’s infrastructure and identifying the human elements linking its various online presences.

Additional Infrastructure Identifiers

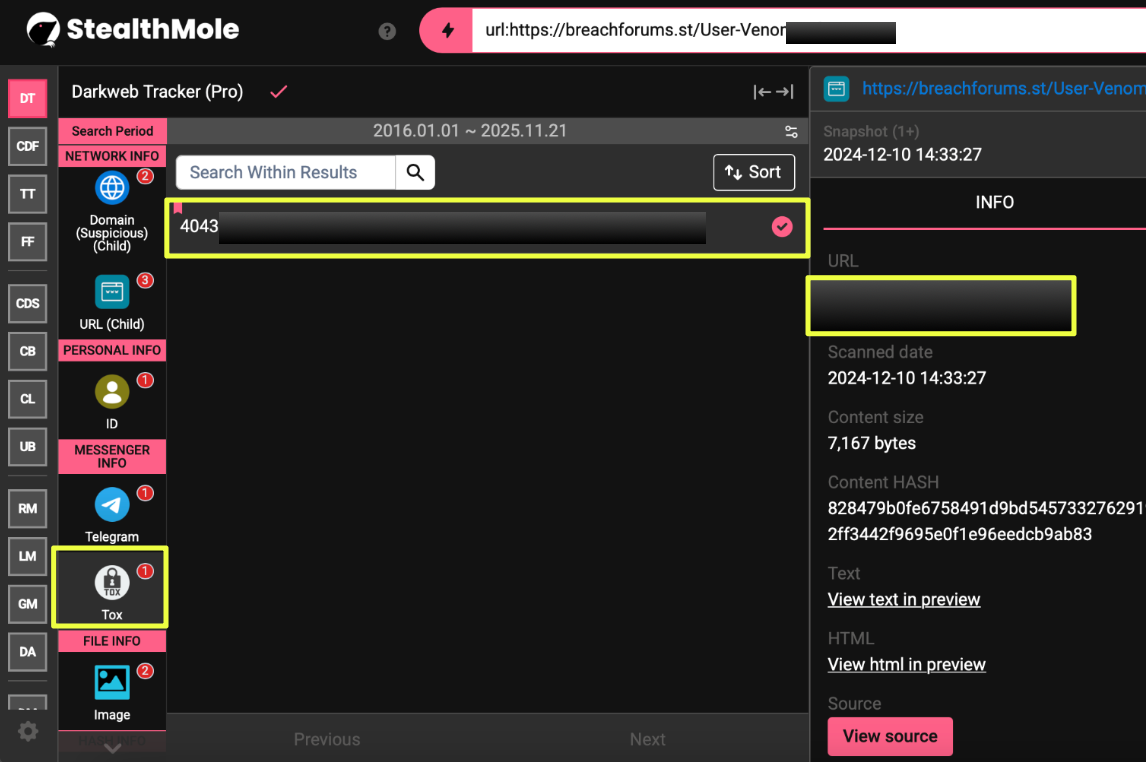

While much of the VenomRAT ecosystem could be mapped through its web infrastructure, Telegram channels, and compromised administrative accounts, several remaining identifiers surfaced during the investigation that further expanded the operational profile of the service. These artifacts did not appear within the public-facing components but were instead uncovered through darkweb pivots and forum-linked traces.

One of the most significant was a TOX ID published on the BreachForums profile associated with the VenomRAT operator. The ID served as an alternative contact channel and appeared alongside the same branding and terminology used across VenomRAT’s Telegram and clearnet infrastructure. TOX identifiers are typically stable and persistent, offering a rare and durable link between accounts even when other platforms are cycled or removed.

- 4043*****************************************************E

The same BreachForums thread also contained a session ID not seen elsewhere in the ecosystem suggesting active forum authentication at the time of the post and further tying the operator’s forum activity to their broader digital footprint.

- 05958c***************************************************346

Separate pivots on the hidden services uncovered additional financial traces. Two Bitcoin addresses were found embedded within Tor-hosted Venom pages:

- 1Hh**************************************b

- bc1*************************************ft

The first address showed minor on-chain activity consistent with small test transactions, while the second appeared in a static context on one of the onion domains, without any confirmed operational use. Although neither wallet reflected meaningful revenue flow, their presence confirmed that at least some parts of the VenomRAT ecosystem incorporated cryptocurrency-based payment or verification elements.

Individually, these identifiers do not offer the same structural insight as the domains, emails, or compromised administrative accounts detailed earlier in the report. However, collectively they form the remaining edges of the VenomRAT cluster: persistent, cross-platform markers that help complete the outline of the ecosystem and firm up the connections between its public presence, underground activity, and operator-linked environments.

Assessment

The investigation into VenomRAT reveals an ecosystem defined less by technical sophistication and more by widespread operational carelessness. Across every layer of the service, from its public storefront to its administrative accounts, the same pattern emerged: VenomRAT was operated and consumed by individuals who lacked the security maturity typically associated with long-running malware projects. The repeated stealer infections affecting the platform’s own administrators illustrate this clearly. Instead of isolating operational activity, the individuals behind VenomRAT appear to have conducted day-to-day tasks from personal machines that were repeatedly compromised, resulting in a trail of exposed credentials that would not exist in a more disciplined operation.

The customer base displayed similar traits. Many of the leaked environments contained basic tooling, cracked malware builders, and overlapping RAT deployments, suggesting that VenomRAT appealed primarily to lower-tier actors who relied on commodity infrastructure and did not apply the very operational security principles VenomRAT purported to help bypass. This aligns with the inconsistent branding, multiple overlapping contact points, and the reliance on public platforms like Telegram and SellPass, all indicators of an ecosystem driven by accessibility rather than anonymity.

From an investigative standpoint, these weaknesses provided unusual visibility into the operation. StealthMole was able to correlate infrastructure, leaked accounts, and underground profiles not because the operator made mistakes during high-risk activities, but because the entire ecosystem functioned in an environment where infections, reuse, and exposure were routine. VenomRAT survived as long as it did not through resilience or sophistication, but because it operated in a segment of the malware market where hygiene is rarely prioritized and where attackers often compromise each other as readily as they compromise victims.

At a strategic level, this places VenomRAT in a distinct category within the malware-as-a-service landscape: a tool that achieved scale not through complexity, but through accessibility and low barriers to entry. Operation Endgame’s disruption of this ecosystem therefore impacts a wide base of small-scale threat actors who depended on VenomRAT as a turnkey solution. While the arrest of the suspected operator will limit further development, the larger takeaway is how easily the ecosystem surrounding VenomRAT revealed itself once pressure was applied, underscoring the fragility of operations built on compromised personal infrastructure and recycled identities.

Conclusion

The investigation into VenomRAT, conducted alongside the disruptions initiated under Operation Endgame, demonstrates how a seemingly modest malware service can expand into a broad, multi-layered ecosystem sustained by inconsistent operational practices and a transient user base. What began as a single darkweb reference evolved into a map of interconnected services, personal environments, and exposed operational touchpoints that remained active even as law-enforcement action intensified.

Operation Endgame targeted VenomRAT as one of its three major malware ecosystems, yet the visibility gained through this investigation shows that its weaknesses were already embedded long before takedown efforts began. The exposed accounts, fragmented infrastructure, and cross-platform identities revealed a service operating without clear boundaries between its administrators, resellers, and customers, an ecosystem large enough to attract global use but fragile enough for its internal components to leak into public stealer logs.

By reconstructing these interconnected elements through StealthMole, this report captures VenomRAT at a moment when its infrastructure, operators, and community were still active and traceable. While the arrest of the suspected operator and the coordinated seizures under Operation Endgame will likely limit VenomRAT’s future development, the findings here underscore a broader reality: the malware-as-a-service landscape is often sustained not by professionalized threat groups, but by loosely organized networks that expose themselves through the very operational shortcuts that make these tools accessible.

Editorial Note

As with all darkweb investigations, the findings in this report are based strictly on observable infrastructure, archived material, and communication traces surfaced through StealthMole. While this report reconstructs the VenomRAT ecosystem with considerable depth, from its public-facing domains to the exposed environments linked to its operators, it does so without making assumptions about identities or intentions beyond the evidence directly captured. Underground ecosystems evolve quickly, and infrastructure tied to malware services can shift or disappear without notice. Accordingly, this report should be viewed as a snapshot of VenomRAT’s operational landscape in the period surrounding Operation Endgame, rather than a complete account of all activity ever associated with the malware.

To access the unmasked report or full details, please reach out to us separately.

Contact us: support@stealthmole.com

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)