From Defacements to Ransomware: Mapping Bangladesh’s Evolving Cyber Threat Landscape Through the NightSpire Case

|

Bangladesh’s rapidly expanding digital ecosystem has increasingly attracted the attention of cyber threat actors. As government services, financial systems, manufacturing supply chains, and educational institutions continue to digitize, the country’s attack surface has grown significantly. At the same time, uneven cybersecurity maturity across sectors has created opportunities for both opportunistic and organized threat actors to exploit vulnerabilities.

Recent monitoring of Bangladesh-linked cyber incidents reveals a diverse threat environment. Website defacements remain one of the most visible indicators of compromise, frequently targeting public-facing systems such as educational institutions, small businesses, and government portals. These attacks often serve as signals of underlying security weaknesses that can later be leveraged for more serious intrusions. Alongside defacements, ransomware activity has also begun to emerge within the country’s threat landscape, reflecting broader global trends in cybercrime.

This report examines Bangladesh’s evolving digital threat environment through data observed across multiple monitoring sources. By analyzing defacement activity alongside ransomware claims, it becomes possible to identify patterns in how cybercriminal groups discover, target, and exploit organizations within the country.

Building on this broader context, the investigation then narrows its focus to a specific ransomware operation that surfaced during the analysis. By tracing the group’s infrastructure, communication channels, and operational ecosystem, this report provides insight into how international ransomware actors intersect with Bangladesh’s growing cyber threat landscape.

Bangladesh’s Emerging Digital Threat Landscape

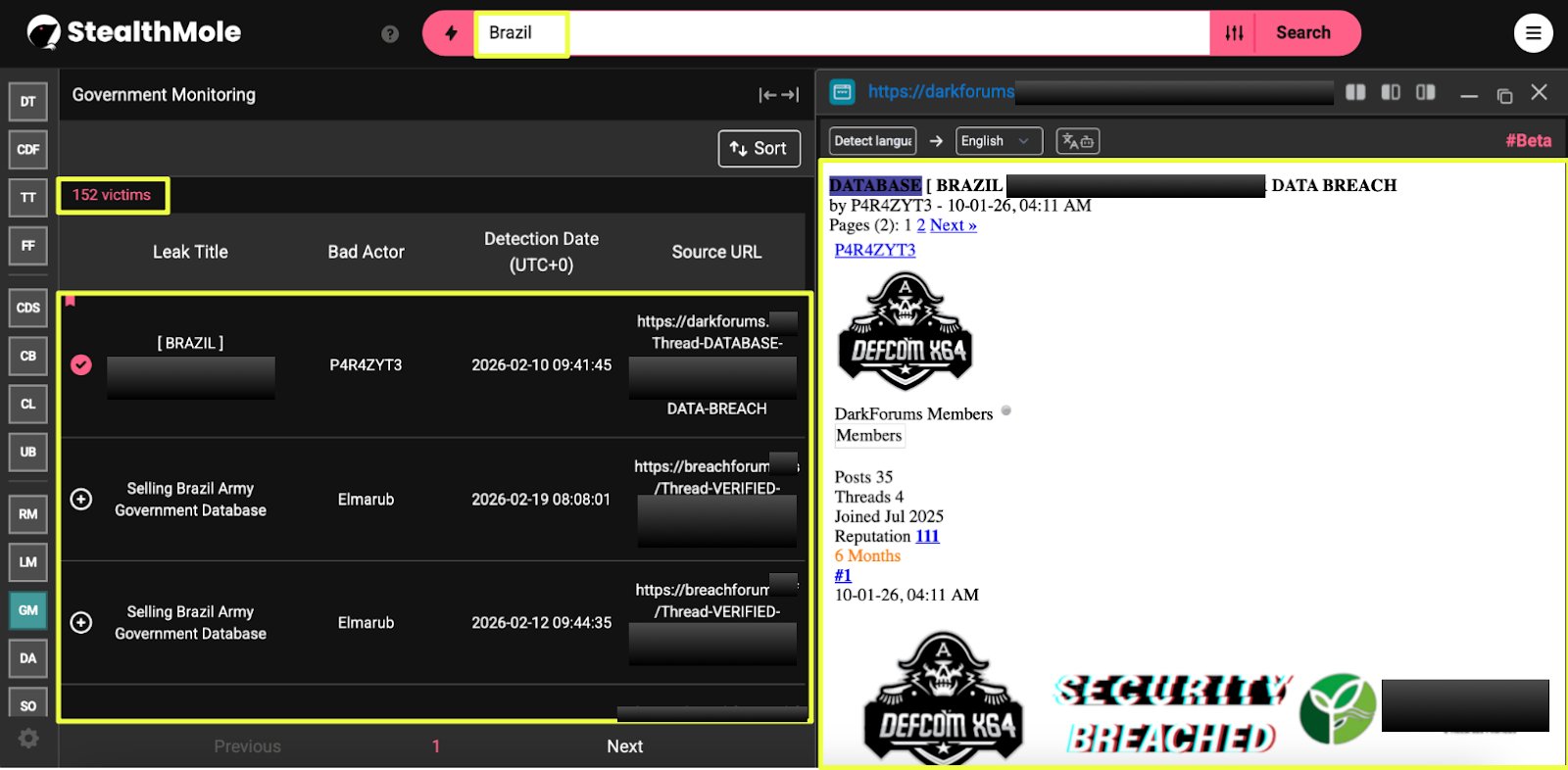

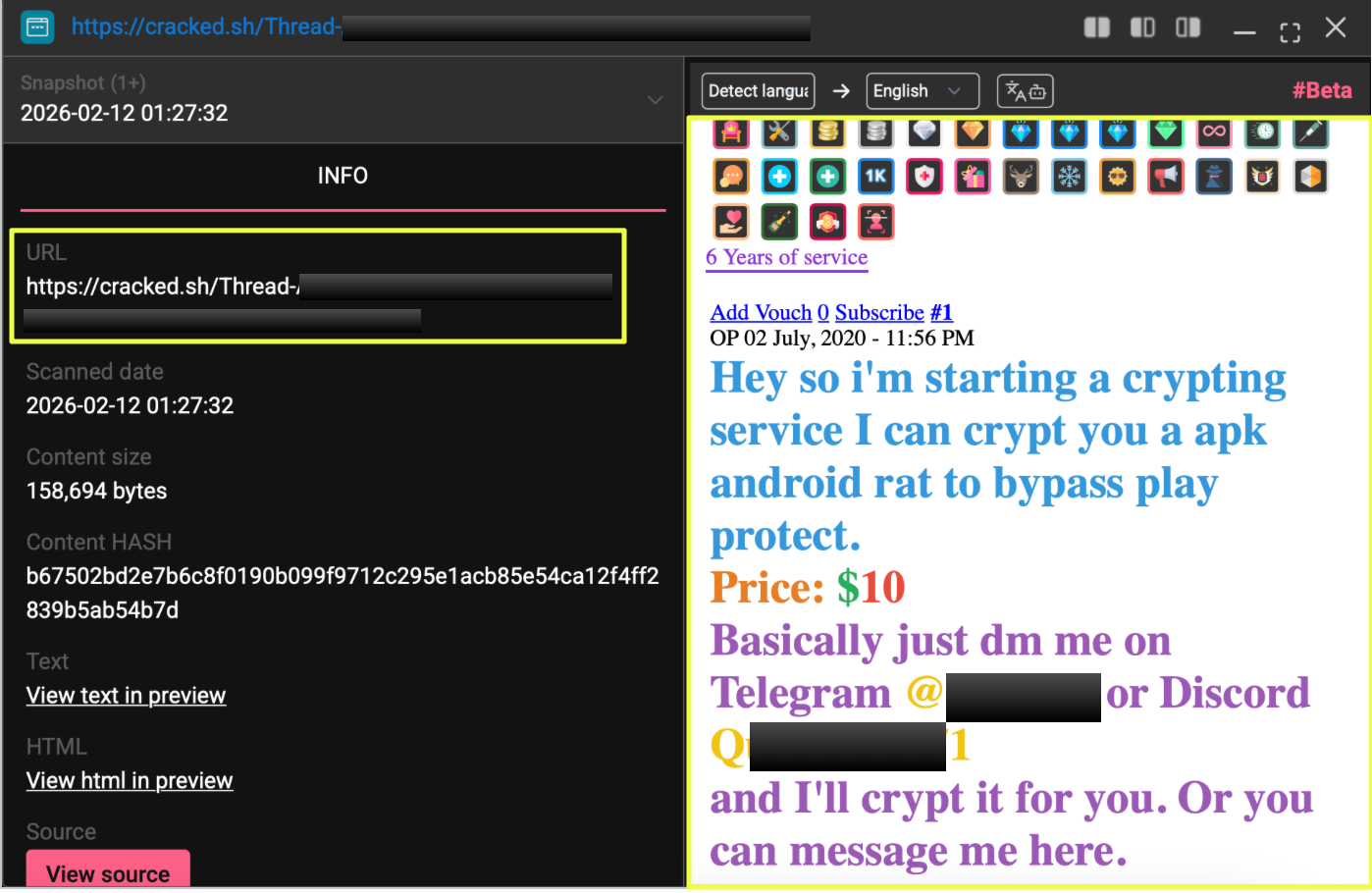

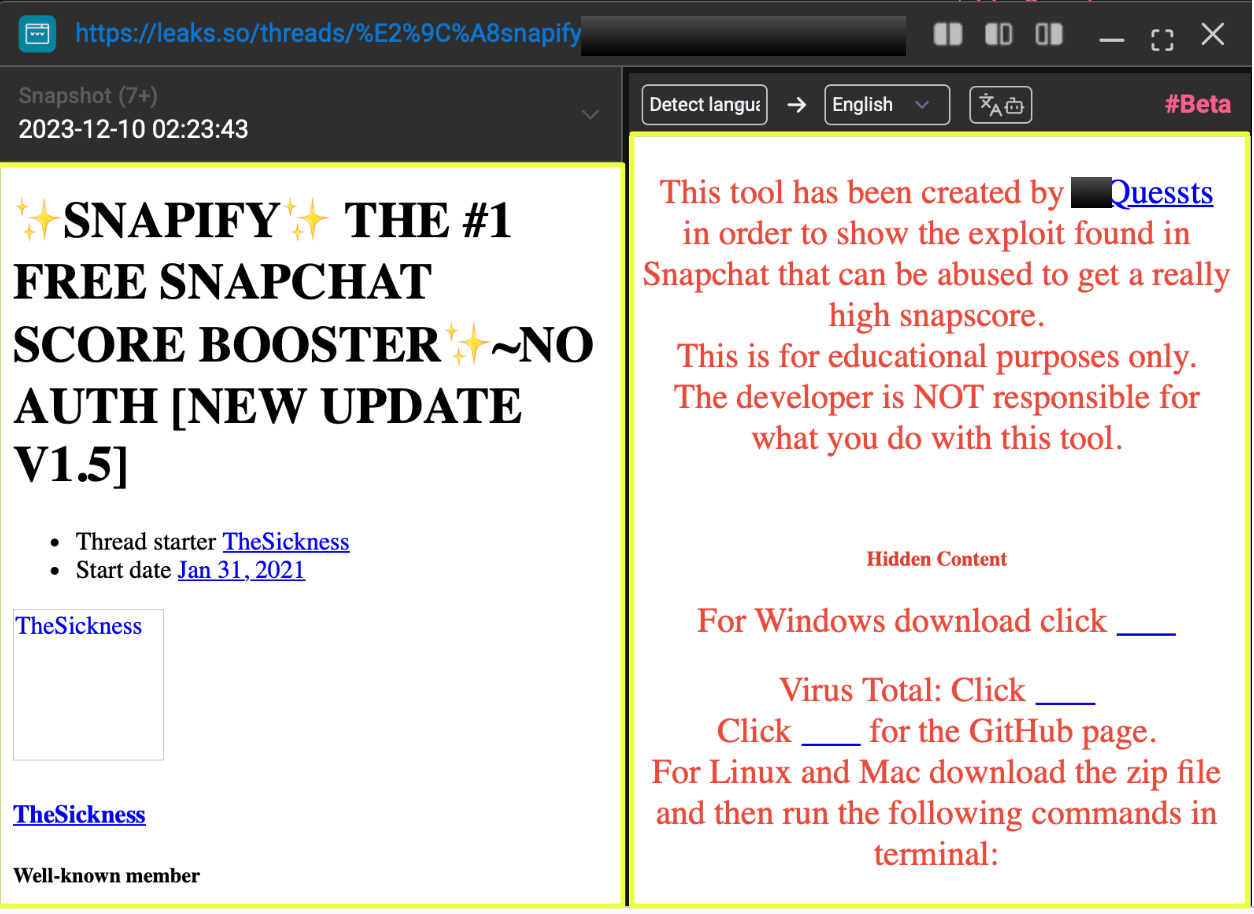

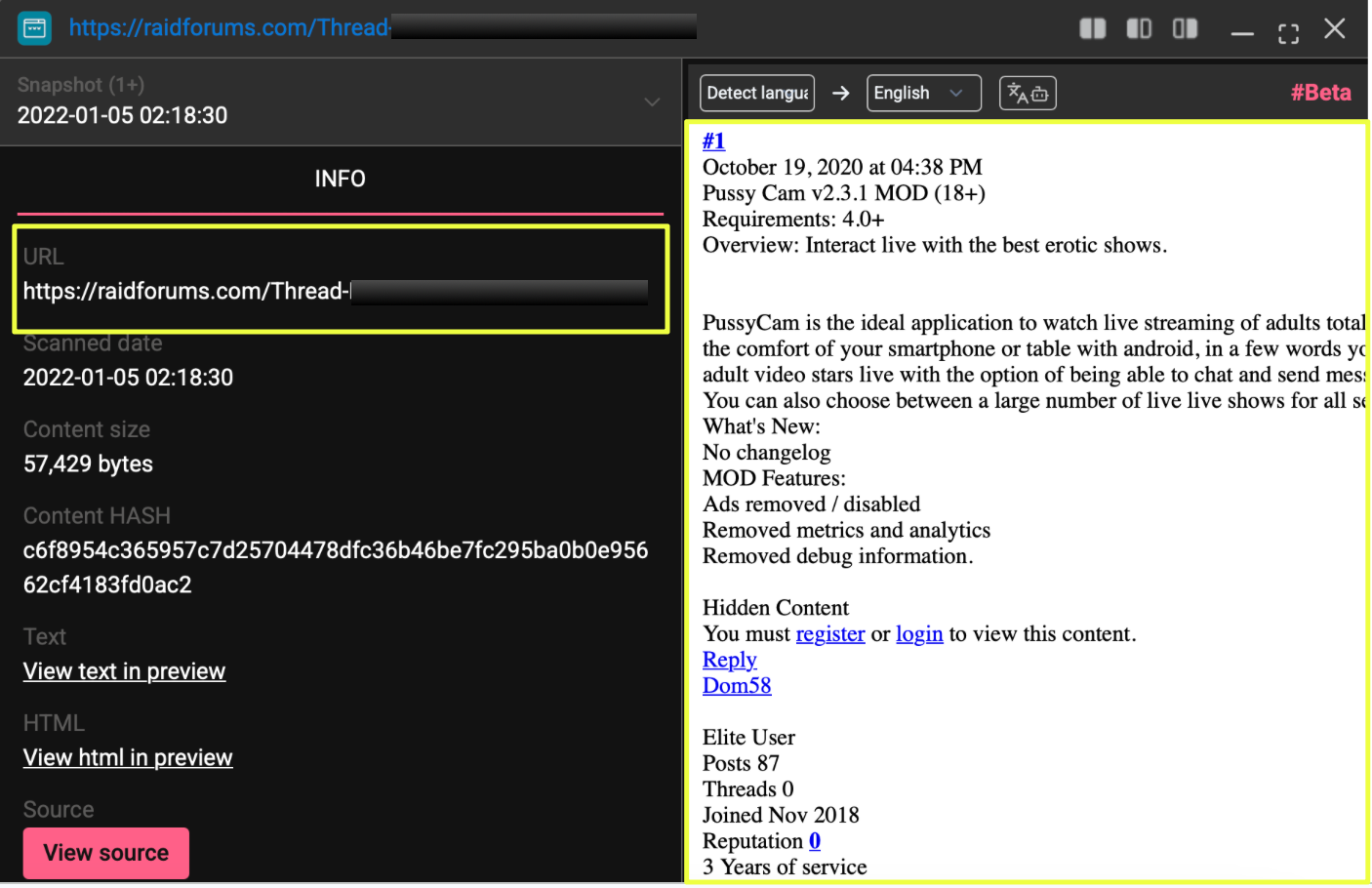

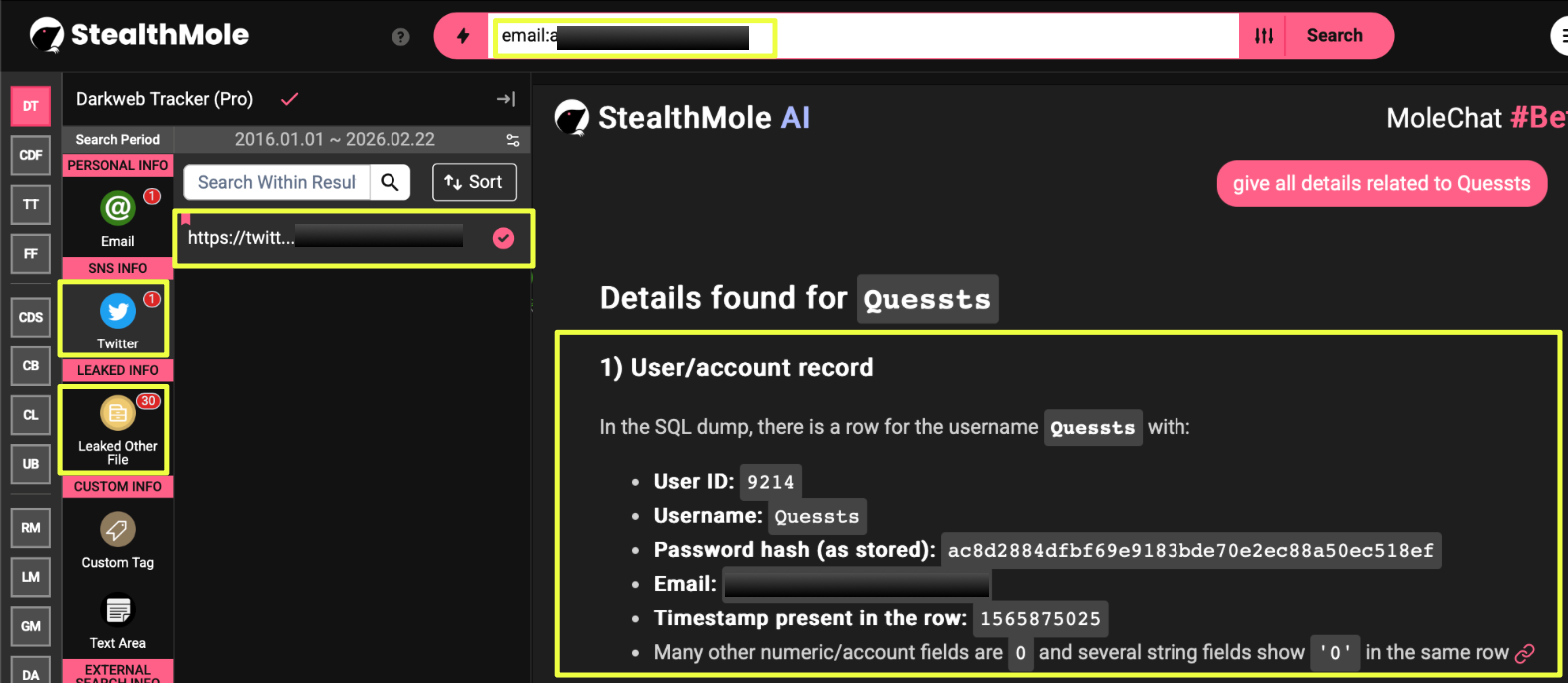

To better understand the scope of cyber activity affecting Bangladesh, StealthMole’s monitoring capabilities were used to examine indicators of compromise across multiple threat intelligence sources. The analysis began with StealthMole’s Defacement Alert (DA) tool, which tracks publicly reported website defacements across the internet.

A search for Bangladesh-linked victims revealed a significant volume of activity. Between January 2023 and March 2026, the DA tool identified approximately 1,512 defacement incidents involving websites hosted in Bangladesh. These incidents span a wide range of sectors, including educational institutions, commercial businesses, and small organizational websites. In many cases, defacements target publicly accessible web servers, often exploiting misconfigured systems, outdated software, or weak administrative protections.

|

While website defacements are sometimes dismissed as low-level cyber vandalism, they often act as an early indicator of deeper security weaknesses. Public-facing vulnerabilities exploited during defacements can expose entry points that more sophisticated threat actors may later leverage for persistent access, data theft, or extortion-based attacks.

To determine whether ransomware activity was also present within Bangladesh’s threat environment, the investigation expanded to StealthMole’s Ransomware Monitoring (RM) tool. This platform aggregates ransomware leak site data, tracking victims claimed by various ransomware groups across the dark web.

The results showed that ransomware groups have also targeted organizations in Bangladesh. Between May 2021 and January 2026, the RM tool recorded 22 ransomware victims associated with entities located in Bangladesh. These incidents involve multiple ransomware groups and affect organizations operating in sectors such as manufacturing, retail, and corporate services.

|

Although the number of ransomware victims appears smaller compared to defacement incidents, ransomware operations typically represent far more damaging intrusions. These attacks often involve network compromise, data exfiltration, and extortion campaigns that can disrupt operations and expose sensitive information.

Among the victims identified during this review, one case in particular stood out during the analysis and became the starting point for a deeper investigation into the ransomware ecosystem connected to Bangladesh.

Incident Trigger and Initial Investigation

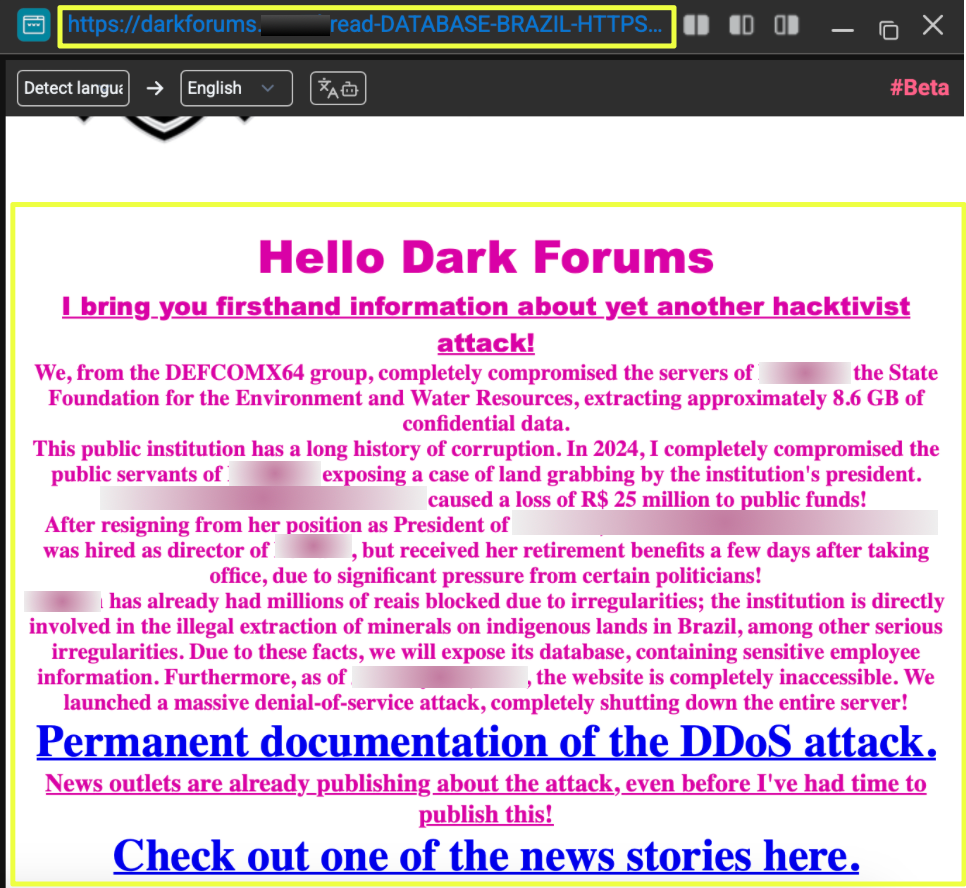

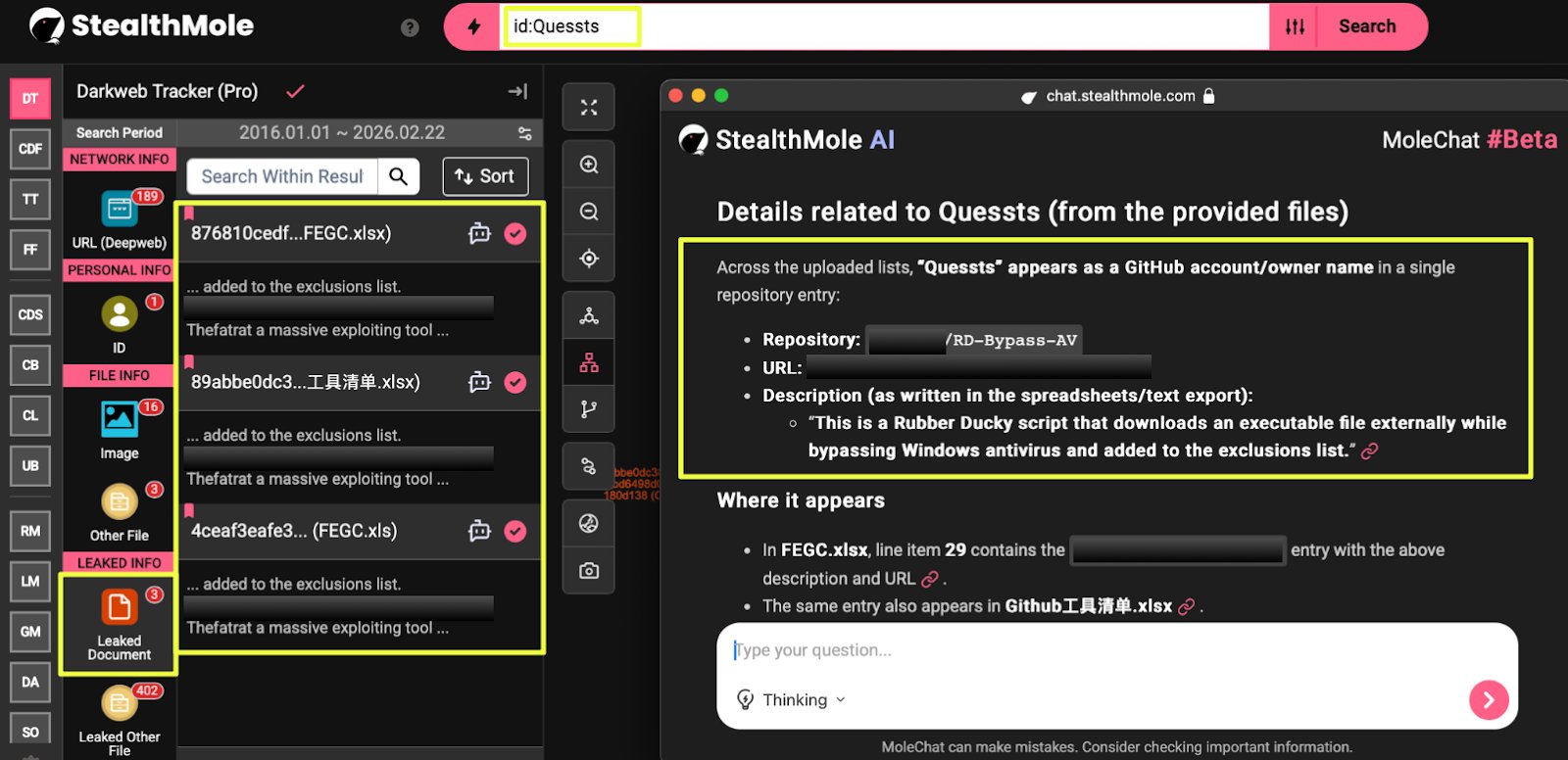

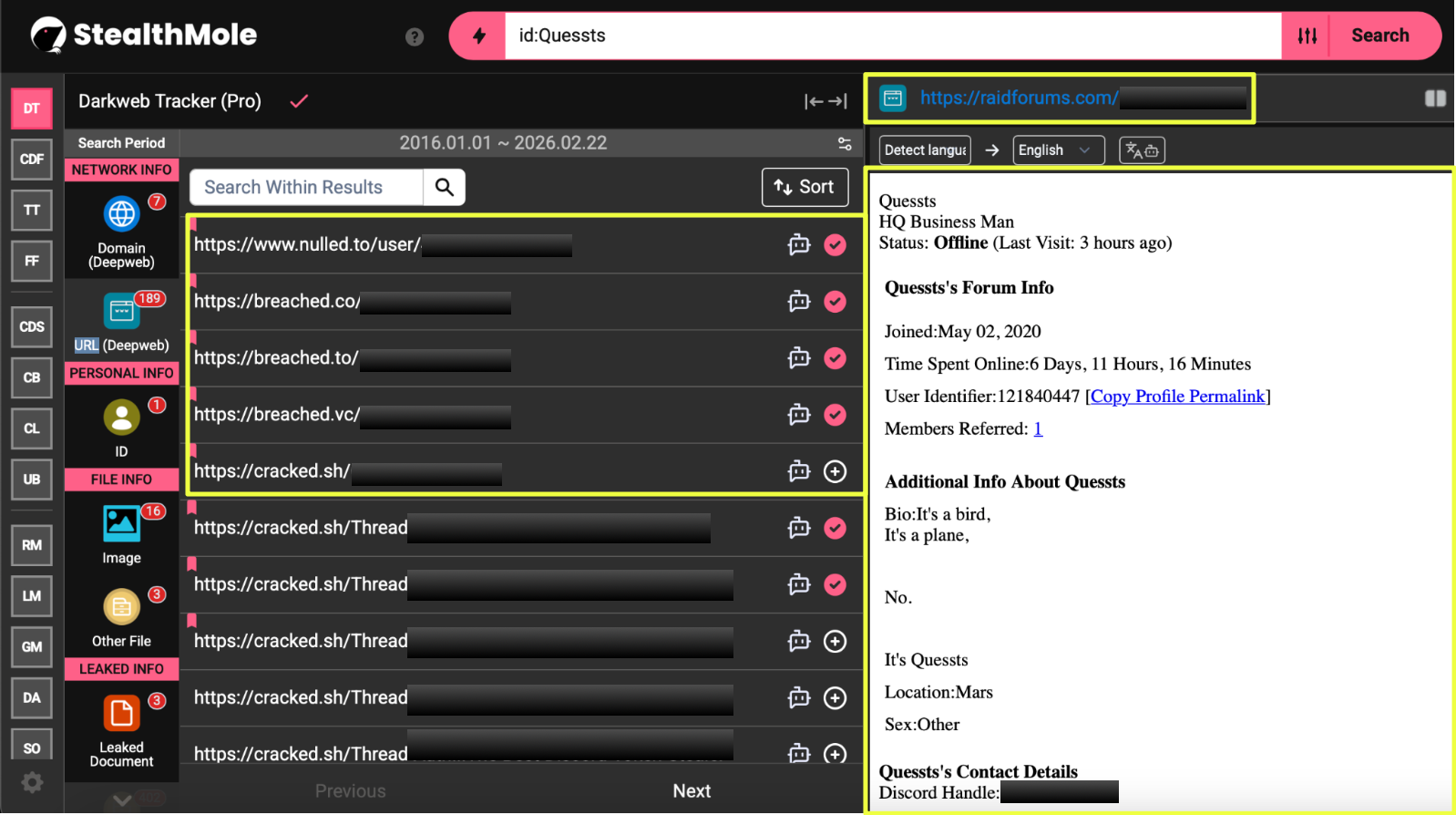

Following the broader review of Bangladesh’s ransomware exposure using StealthMole’s Ransomware Monitoring (RM) module, one listing in particular stood out during the analysis. StealthMole identified a Bangladesh-based textile manufacturing company, as a victim claimed by the ransomware group NightSpire.

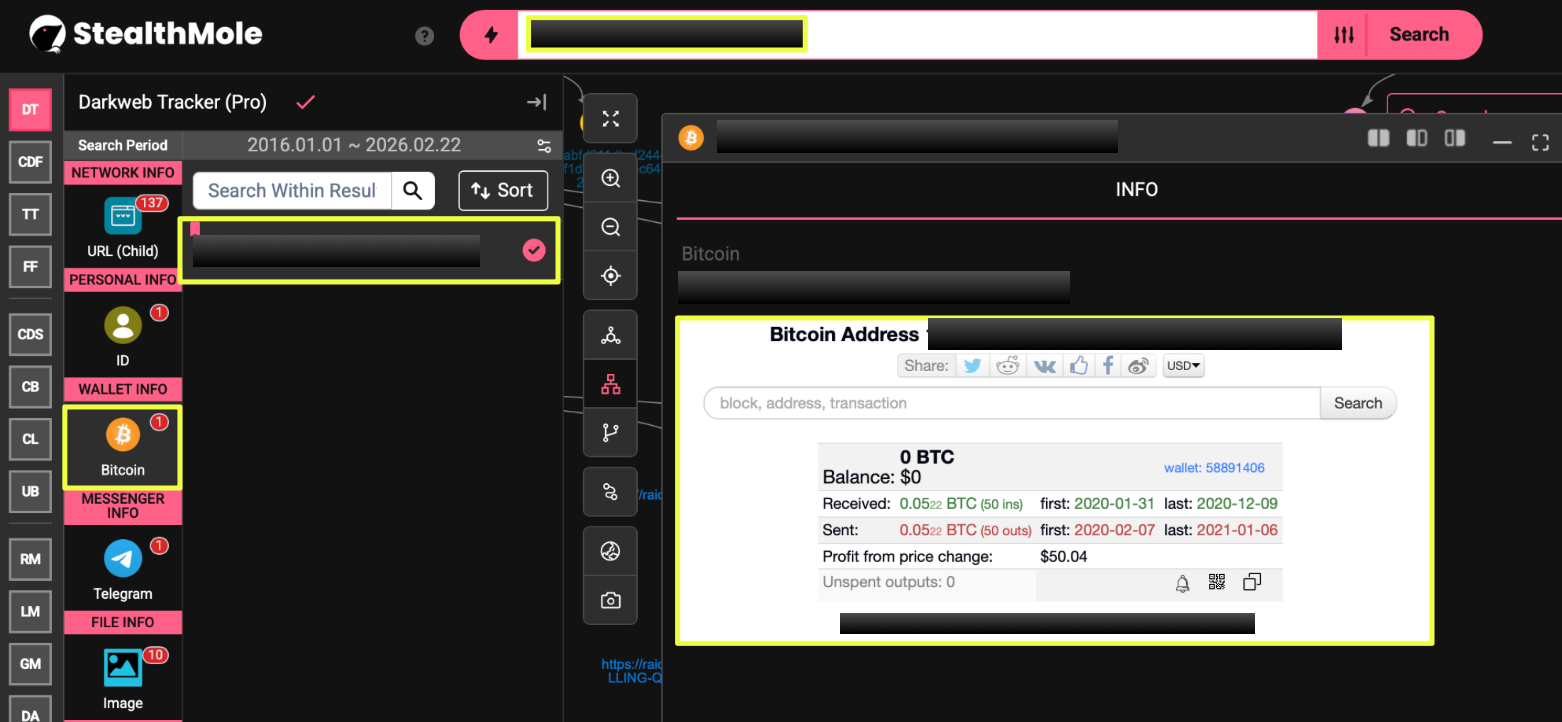

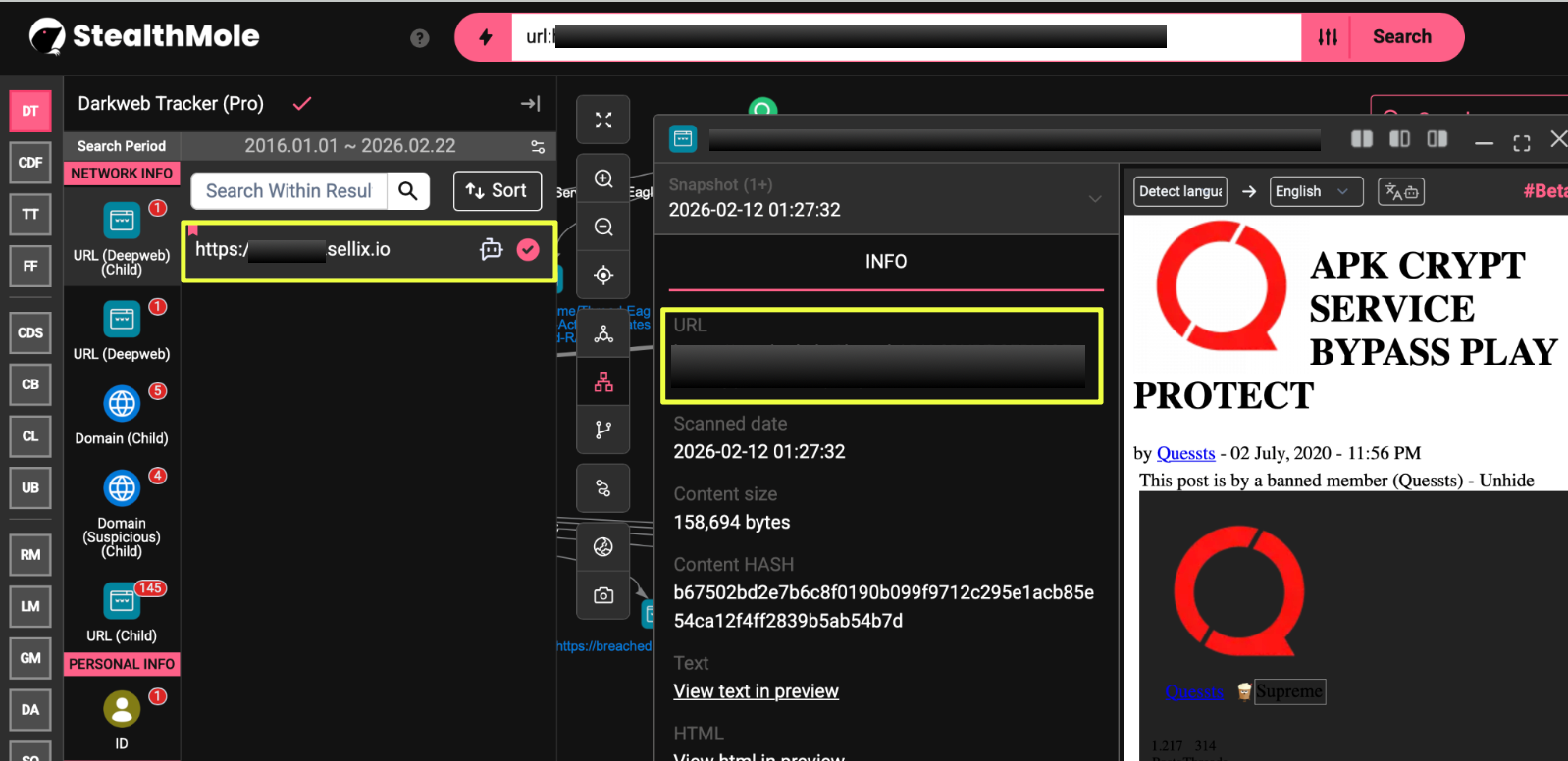

To investigate the threat actor responsible for the claim, the analysis shifted toward NightSpire’s infrastructure. Using StealthMole’s Dark Web Tracker, the ransomware group’s leak site was identified at:

- a2lyiiaq4n74tlgz4fk3ft4akolapfrzk772dk24iq32cznjsmzpanqd.onion

|

Snapshots captured from the site revealed the group publicly threatening organizations whose data had allegedly been stolen. One message posted on the platform stated that 1TB of data had been copied from a victim organization, warning that the information would be released publicly if negotiations did not take place within a specified timeframe. The site also included sample records and download links intended to demonstrate the authenticity of the stolen data.

Further examination of the leak site indicated that NightSpire was not operating solely as a ransomware actor but was actively promoting a Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) model. The platform openly advertised opportunities for affiliates to join the operation, suggesting that the group was attempting to expand its network of operators and increase the scale of its attacks.

This discovery prompted a deeper investigation into the group’s infrastructure, communication channels, and recruitment activities across the dark web ecosystem.

Mapping the NightSpire Ransomware Infrastructure

After identifying NightSpire as the ransomware group claiming the compromise of Premier 1888 Ltd., the investigation shifted toward understanding the broader infrastructure used by the group. Rather than relying solely on a single leak portal, StealthMole analysis revealed that NightSpire maintains a network of interconnected onion domains, communication channels, and file-hosting infrastructure that together support its ransomware operations.

The investigation therefore expanded to map these elements and determine how the group structures its operational ecosystem.

Primary Leak Site Infrastructure

The initial pivot began with the leak site identified through StealthMole’s Ransomware Monitoring module:

- a2lyiiaq4n74tlgz4fk3ft4akolapfrzk772dk24iq32cznjsmzpanqd.onion

StealthMole records indicate that this domain functioned as one of NightSpire’s primary leak portals. The page structure included listings of victim organizations, descriptions of stolen data, and timestamps indicating when intrusions allegedly occurred. The site also displayed warnings to victims that stolen data would be publicly released if negotiations failed.

The portal followed a pattern commonly seen in ransomware leak platforms, where attackers attempt to pressure victims by publicly advertising compromised organizations and threatening staged data leaks.

Associated Onion Infrastructure

Further analysis of the primary leak domain uncovered additional onion services connected to NightSpire. These domains appear to represent different components of the group’s infrastructure, potentially serving purposes such as leak hosting, negotiation portals, or content distribution.

Two additional domains were discovered through StealthMole’s Dark Web Tracker:

- nspiremkiq44zcxjbgvab4mdedyh2pzj5kzbmvftcugq3mczx3dqogid.onion

- nspirebcv4sy3yydtaercuut34hwc4fsxqqv4b4ye4xmo6qp3vxhulqd.onion

Both domains were inactive at the time of analysis. However, historical snapshots suggest they previously hosted content associated with the NightSpire operation.

|

|

Further investigation revealed an additional onion service:

- nspire7lugml7ybqyjaaxtsgrs4qn3fcon3lrjbih6wamttvdm5ke4qd.onion

|

This page appeared to function as a NightSpire chat or negotiation portal, requiring visitors to complete a CAPTCHA verification before accessing the communication interface.

Another domain later identified through Telegram-linked references was:

- nspirep7orjq73k2x2fwh2mxgh74vm2now6cdbnnxjk2f5wn34bmdxad.onion

|

Unlike the earlier infrastructure, this site presented itself as a NightSpire blog and information portal, containing sections for news updates, leaked data, contact information, and affiliate recruitment.

The presence of multiple onion domains suggests that NightSpire operates a distributed infrastructure rather than relying on a single leak platform.

Malware Hashes Linked to the Operation

StealthMole’s Dark Web Tracker also revealed six malware hashes associated with the NightSpire infrastructure. These hashes likely correspond to files distributed through the group’s ecosystem, potentially including ransomware payloads, tooling, or related operational artifacts.

The identified hashes include:

- d5f9*********************************************a6

- c285*********************************************53

- e275*********************************************3d

- 32e1*********************************************a5

- f017*********************************************a1

- dbf0*********************************************d7

|

- nspiremkiq44zcxjbgvab4mdedyh2pzj5kzbmvftcugq3mczx3dqogid.onion

This overlap indicates that multiple NightSpire domains may distribute or reference the same set of malicious files, reinforcing the likelihood that these domains belong to a unified operational infrastructure.

External File Hosting Infrastructure

In addition to onion-hosted resources, the investigation identified nine MEGA file-hosting links associated with the NightSpire infrastructure.

|

The use of external cloud storage platforms is a tactic frequently observed in ransomware operations. These services may be used to host:

- sample data used as proof of compromise

- staged data leaks

- operational tooling

- ransomware payload files

Although the exact content of the hosted files was not directly examined during this investigation, the presence of multiple cloud-hosting links suggests that NightSpire supplements its dark web infrastructure with external storage platforms to distribute or archive stolen data.

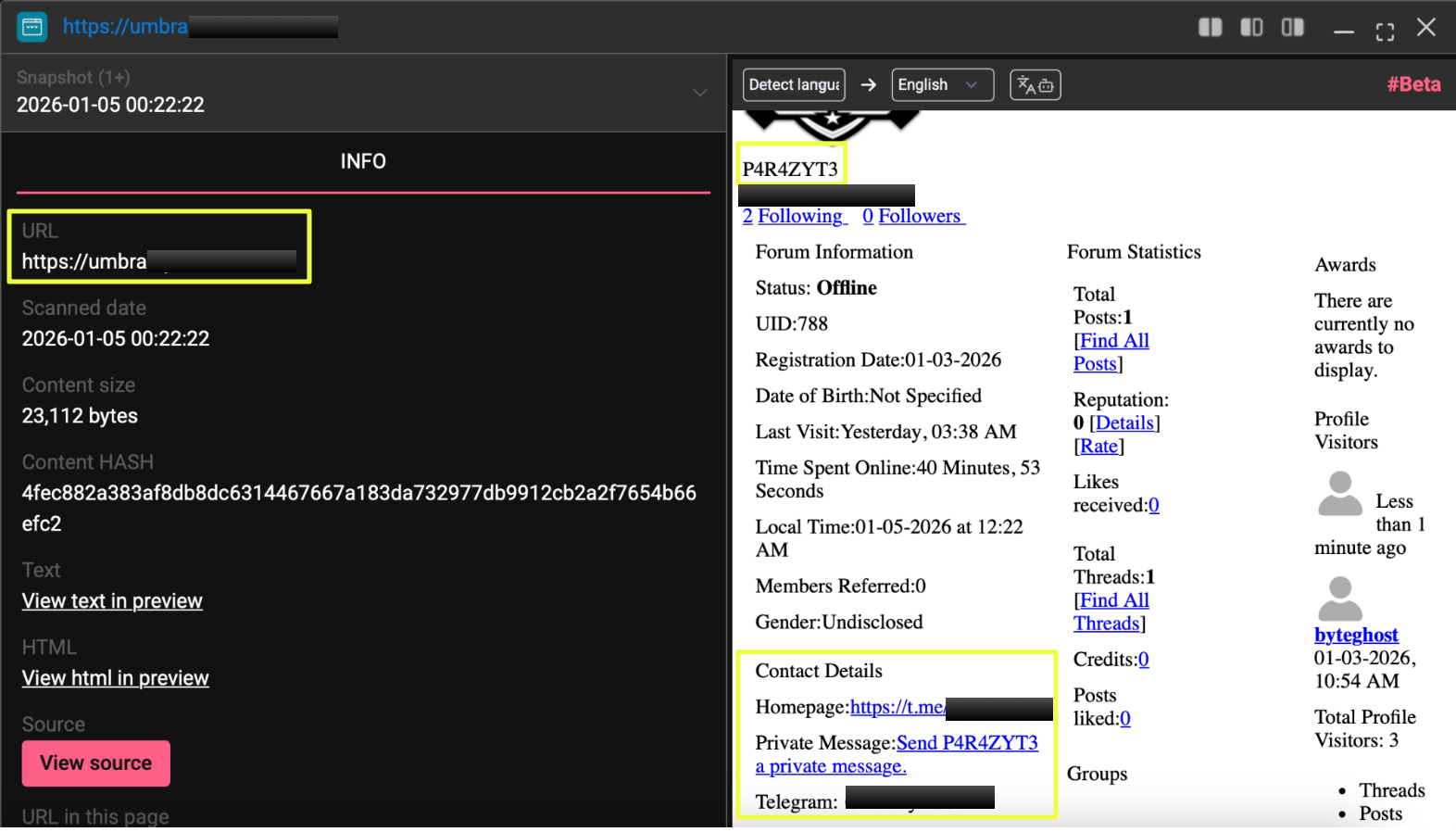

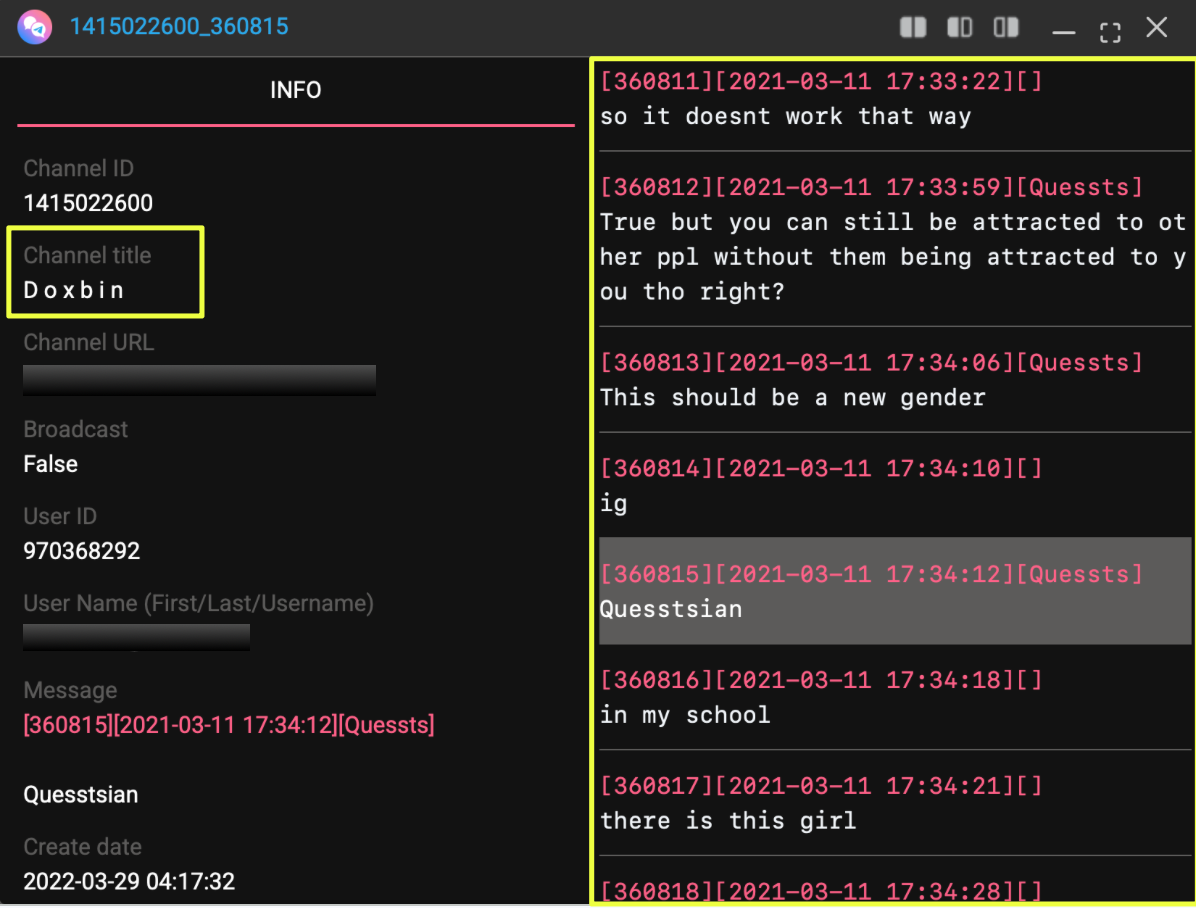

Communication Channels and Contact Identifiers

The NightSpire infrastructure also revealed multiple communication channels intended for negotiations and operational coordination.

The following identifiers were observed across several NightSpire domains:

Email addresses

- nightspire********@onionmail.org

- nightspire************@proton.me

- nightspire*******6@onionmail.org

- nightspire*********6@proton.me

Telegram

- https://t.me/nightspire******5

Notably, the Telegram link pointed to an individual user account rather than a broadcast channel, suggesting that the platform may be used for direct negotiations or private communication.

Session ID

- 057d49****************************************a02

TOX IDs

- 3B61CF**************************************************7E6

- 8D663F**************************************************E7F

- 038F6***************************************************9EA

The presence of multiple encrypted messaging platforms suggests that NightSpire maintains redundant communication methods to ensure continued contact with victims and affiliates even if individual services are disrupted.

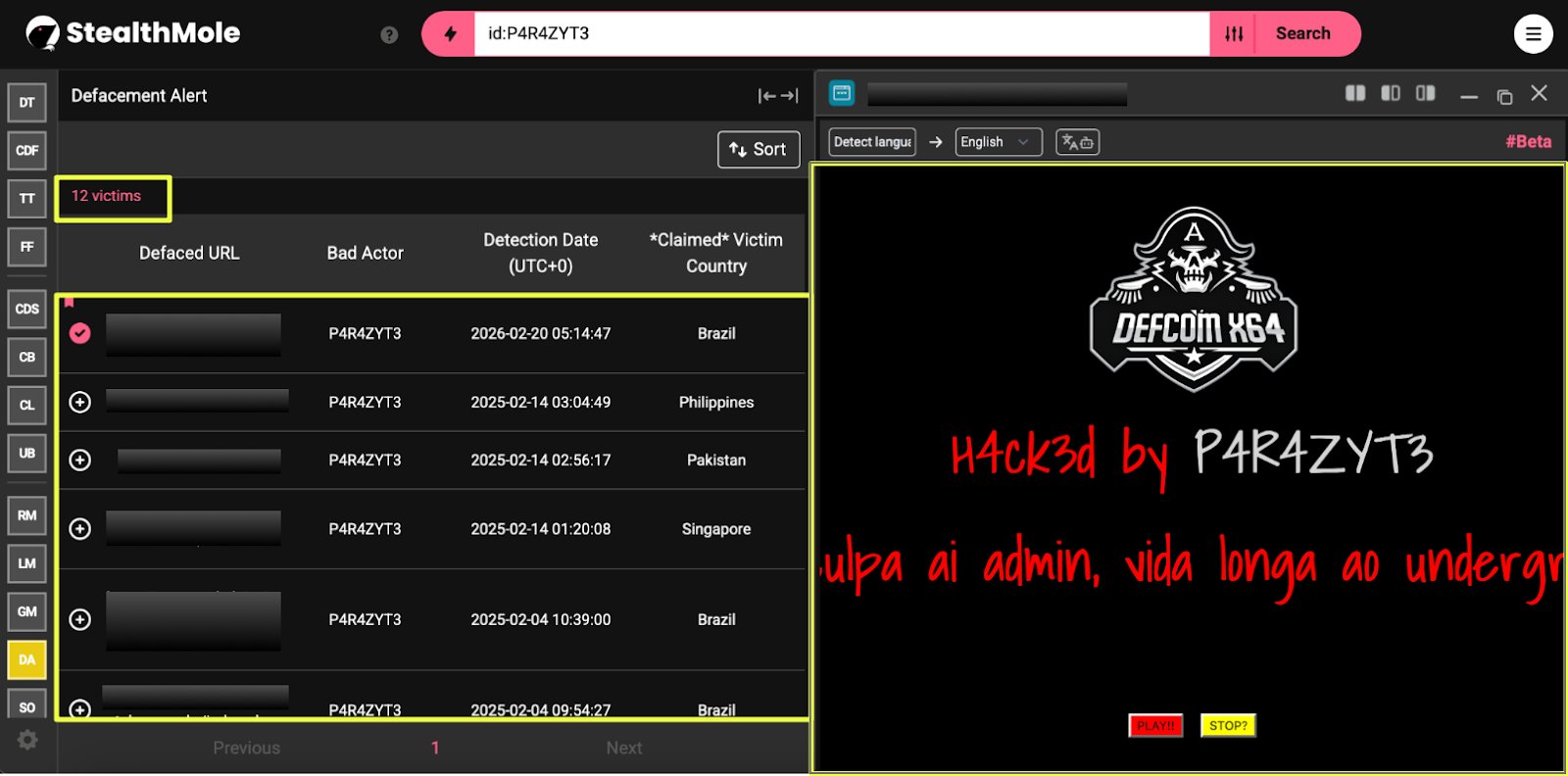

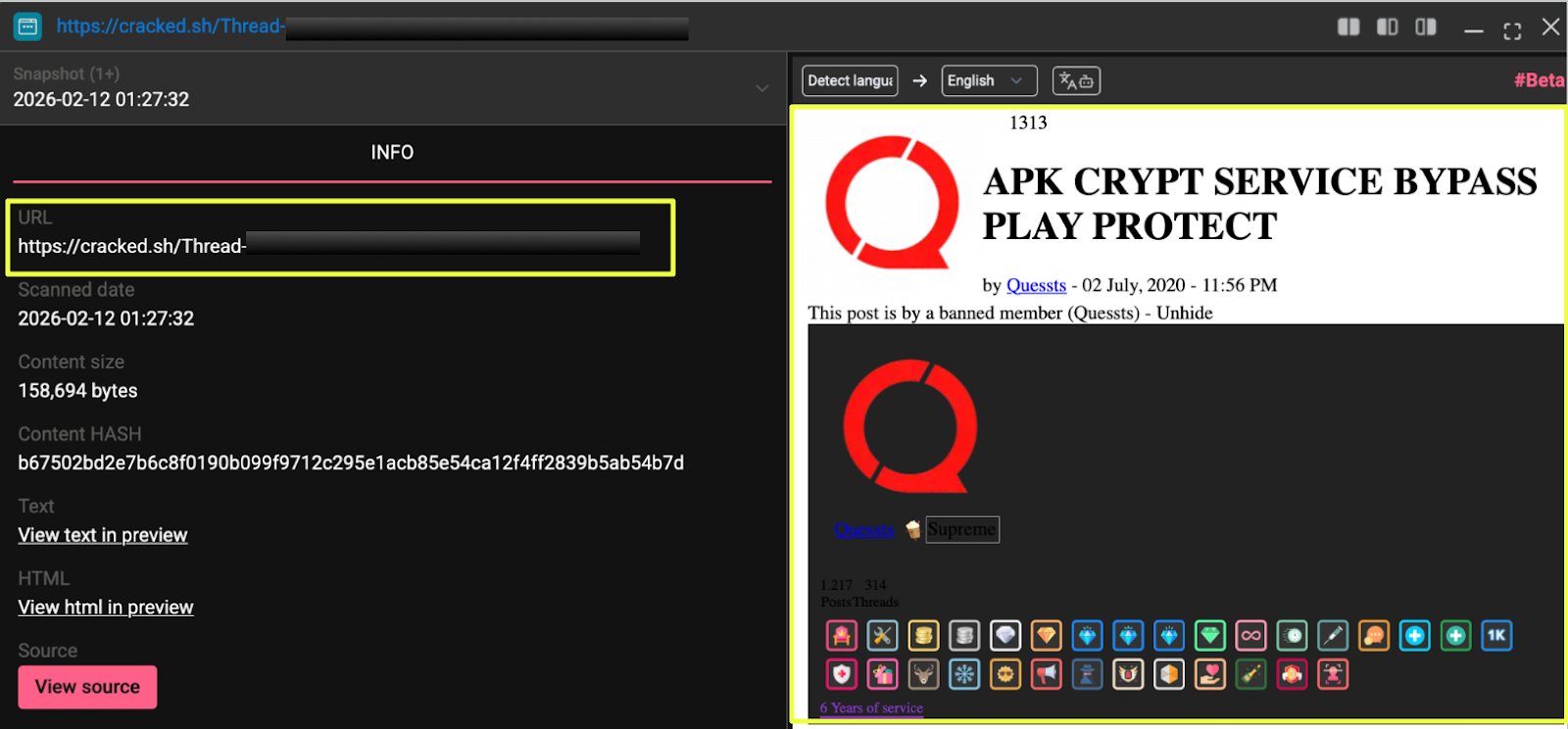

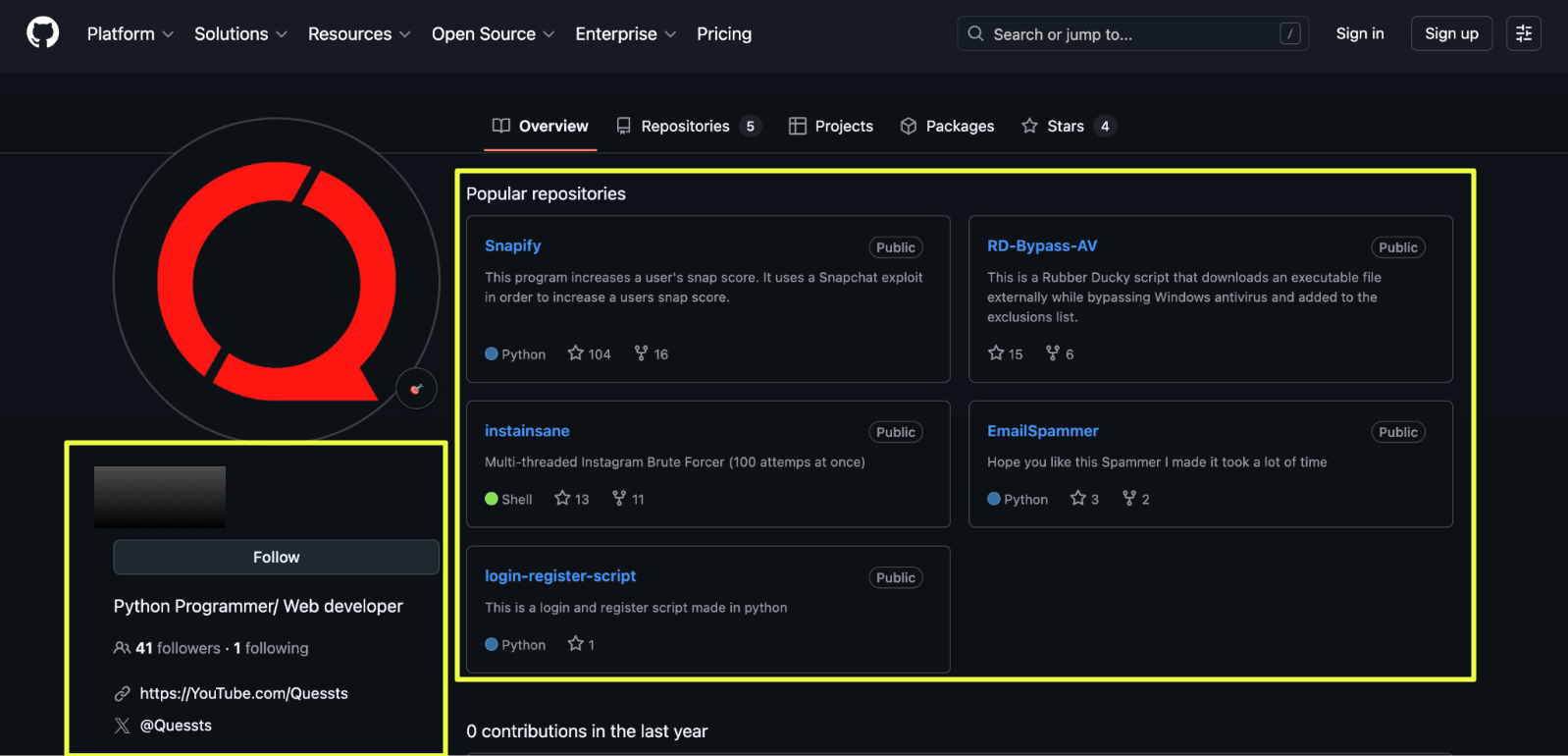

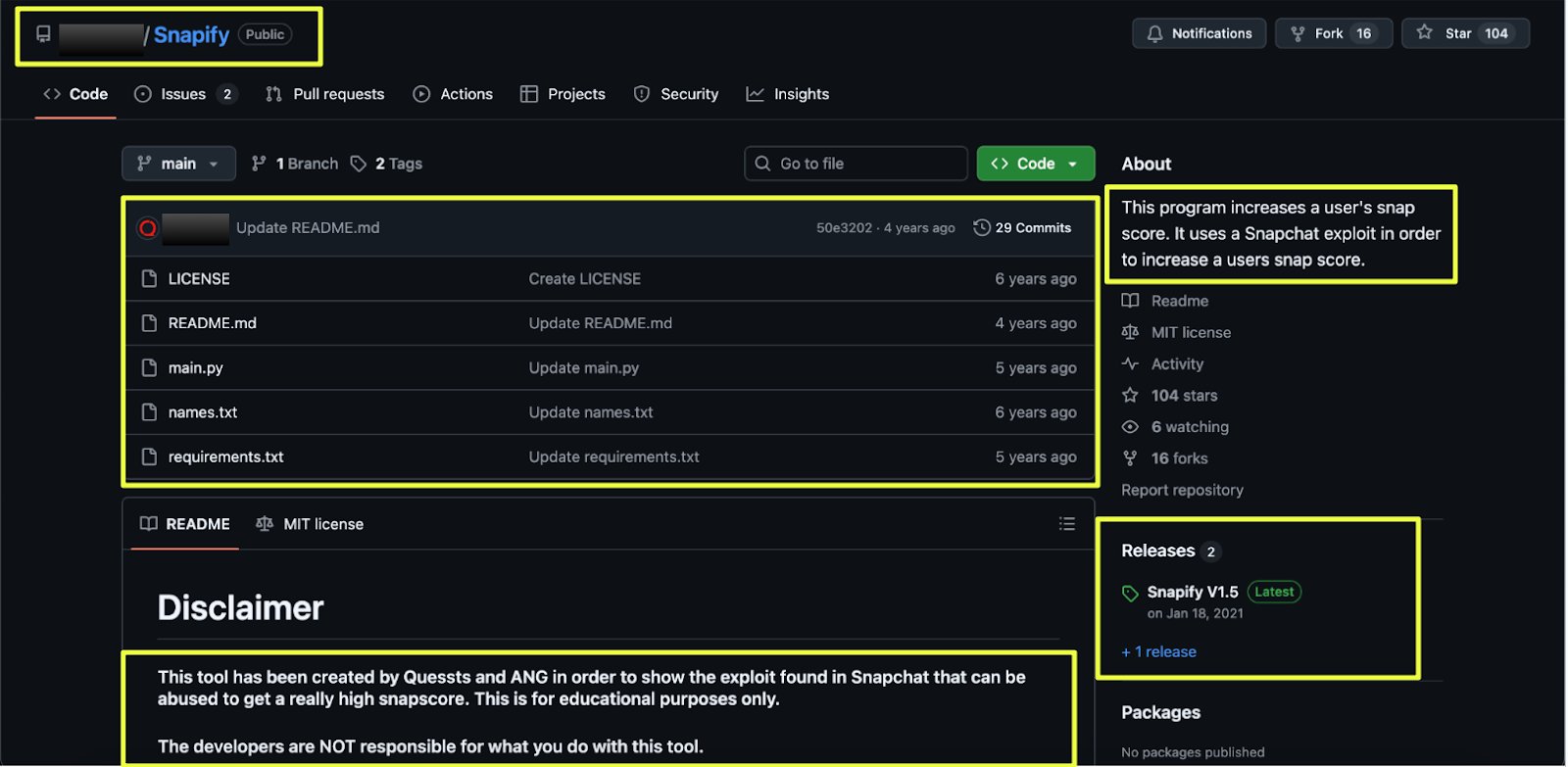

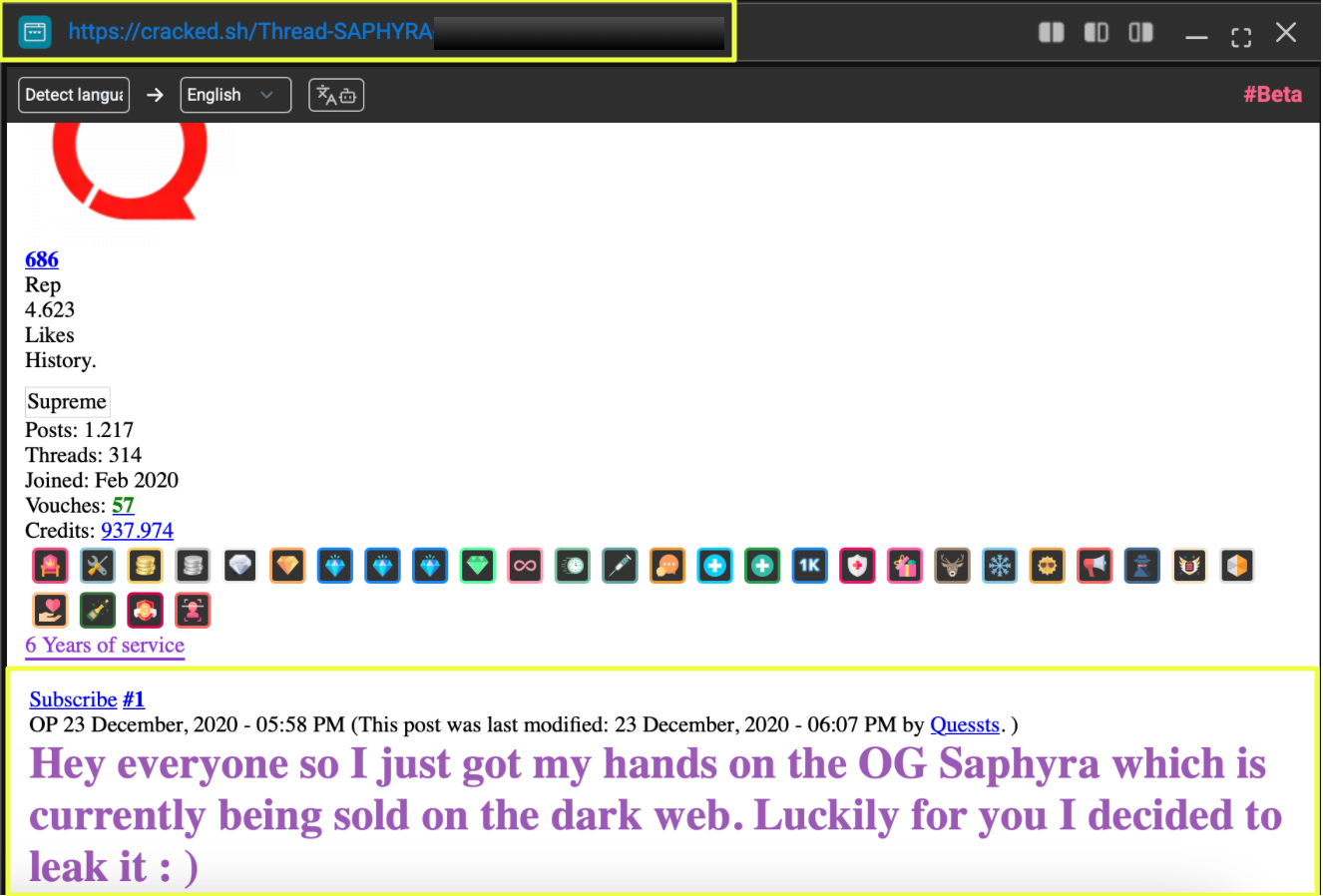

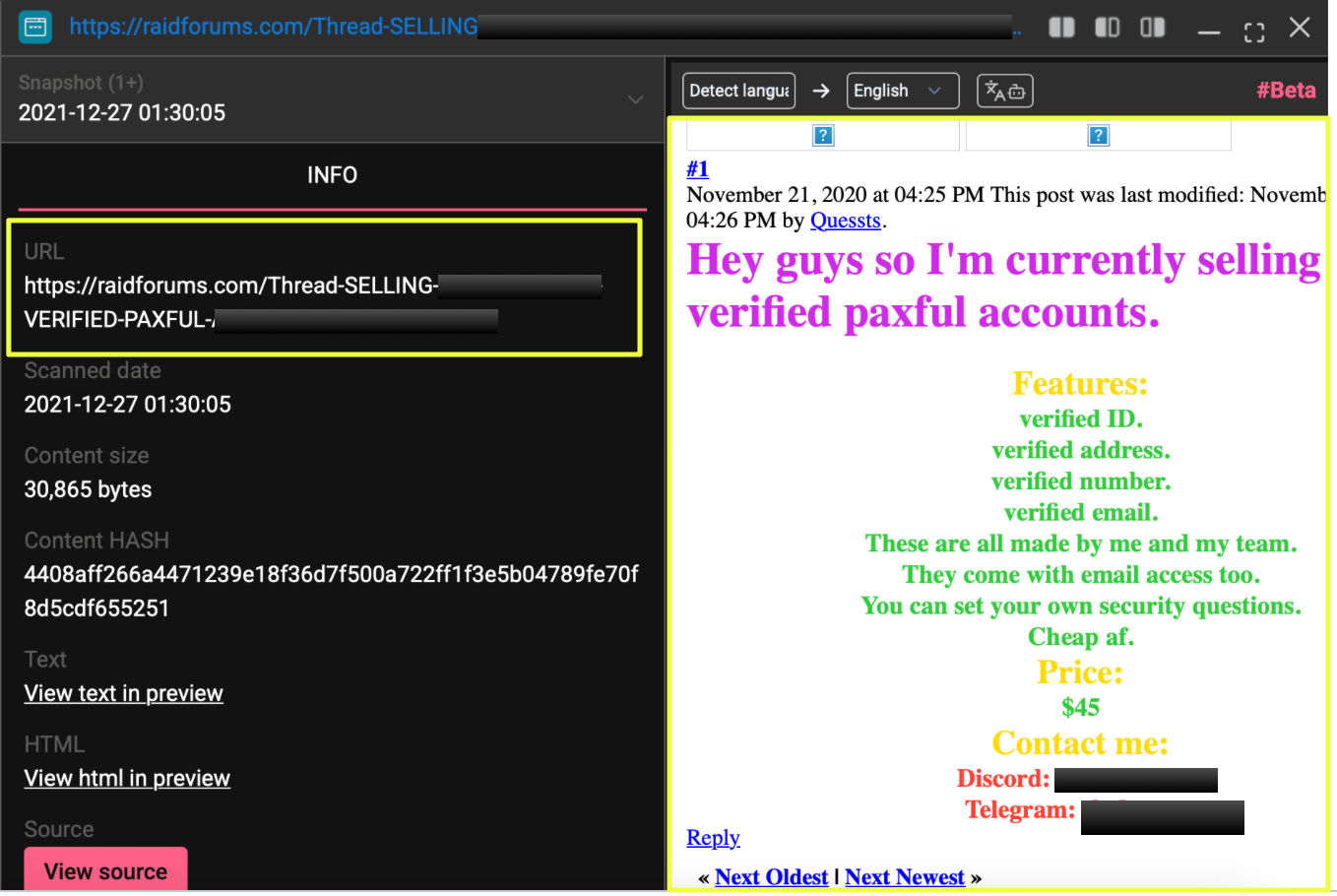

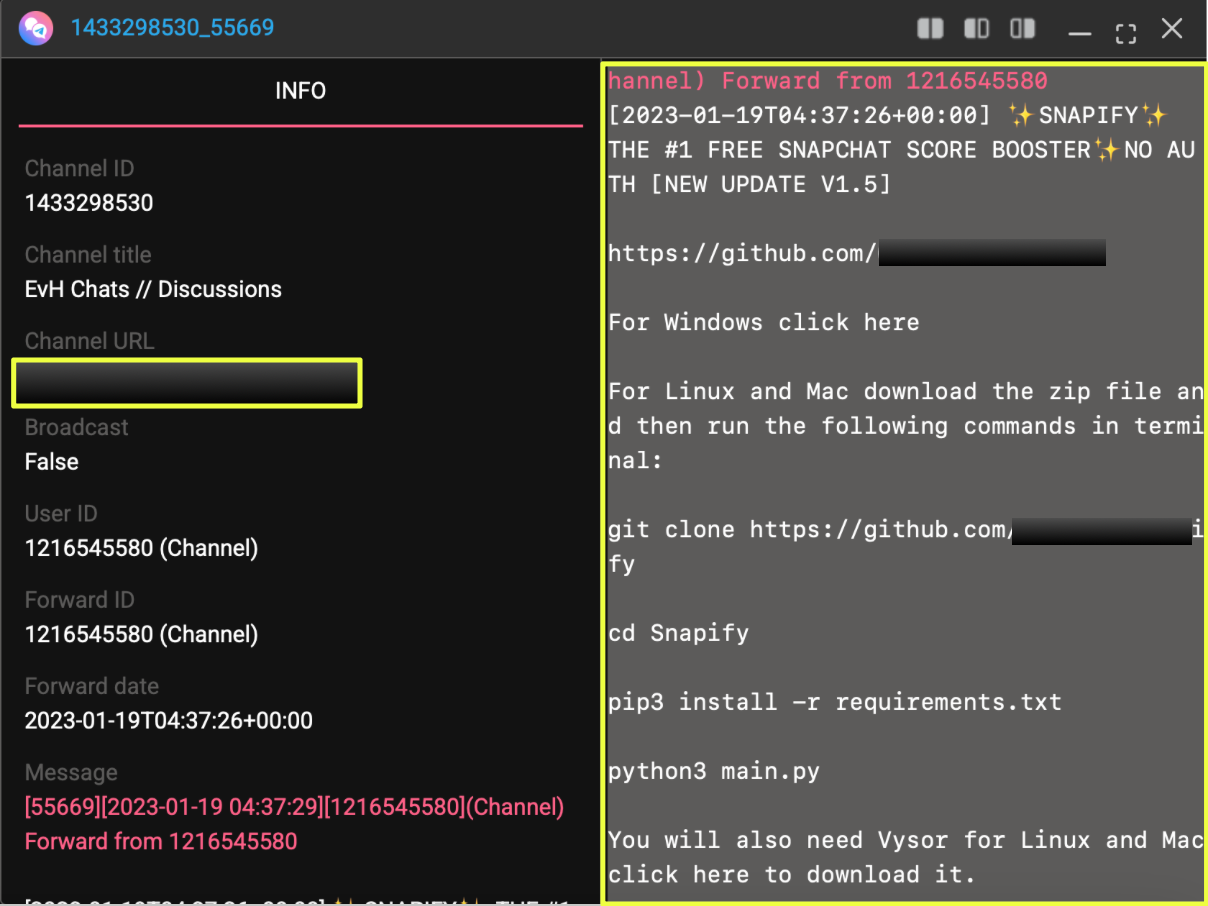

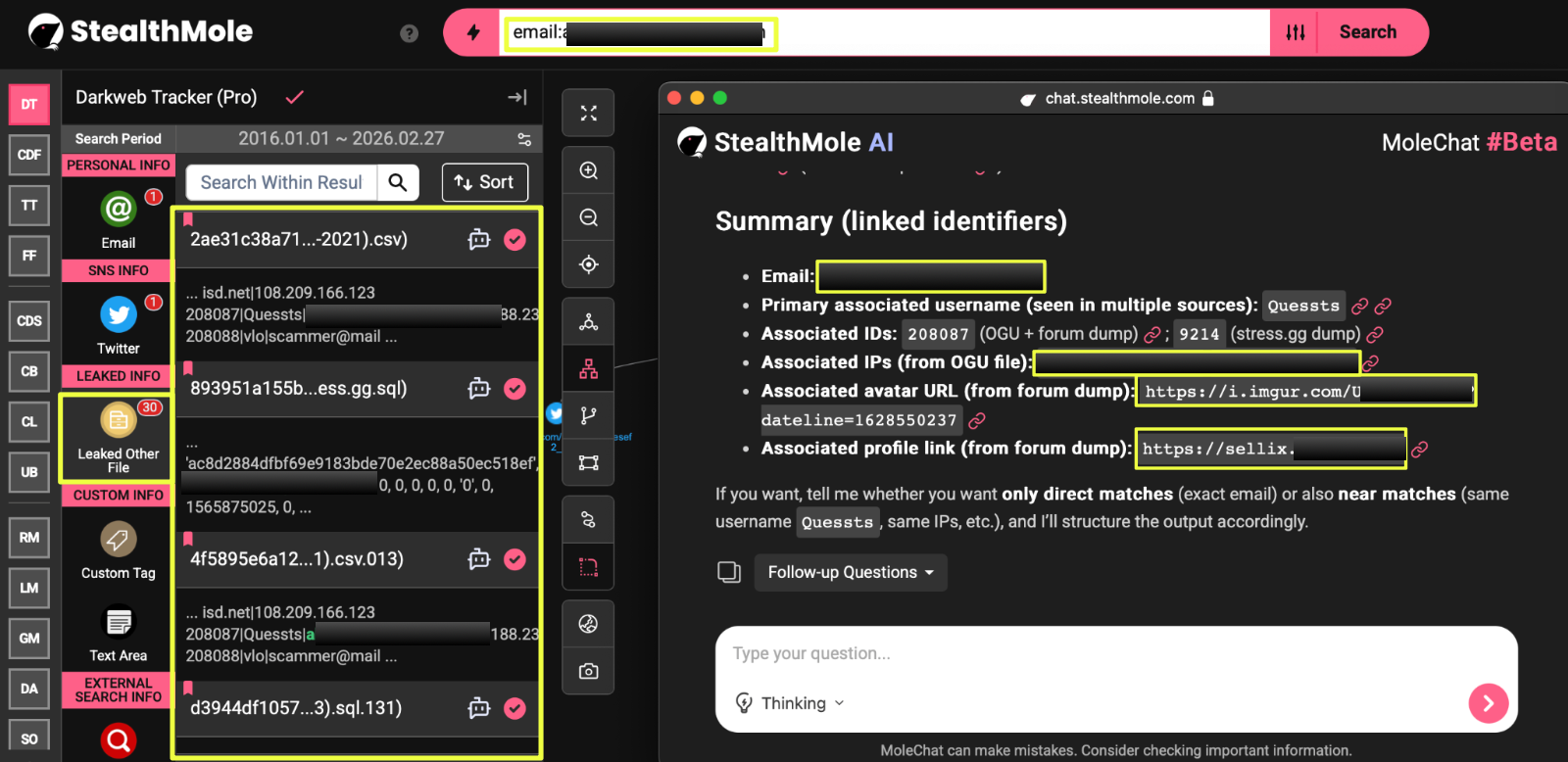

Evidence of Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) Activity

In addition to infrastructure and communication channels, the investigation uncovered indicators suggesting that NightSpire operates under a Ransomware-as-a-Service model.

|

One underground forum discussion referenced NightSpire alongside other ransomware groups as a potential RaaS operation that individuals could join. Additionally, pages discovered within the NightSpire ecosystem contained messages inviting actors to become affiliates and participate in the group’s operations.

This suggests that the group may rely on a decentralized network of affiliates who deploy ransomware using the infrastructure provided by the NightSpire operators.

NightSpire’s Organizational Narrative and Affiliate Recruitment

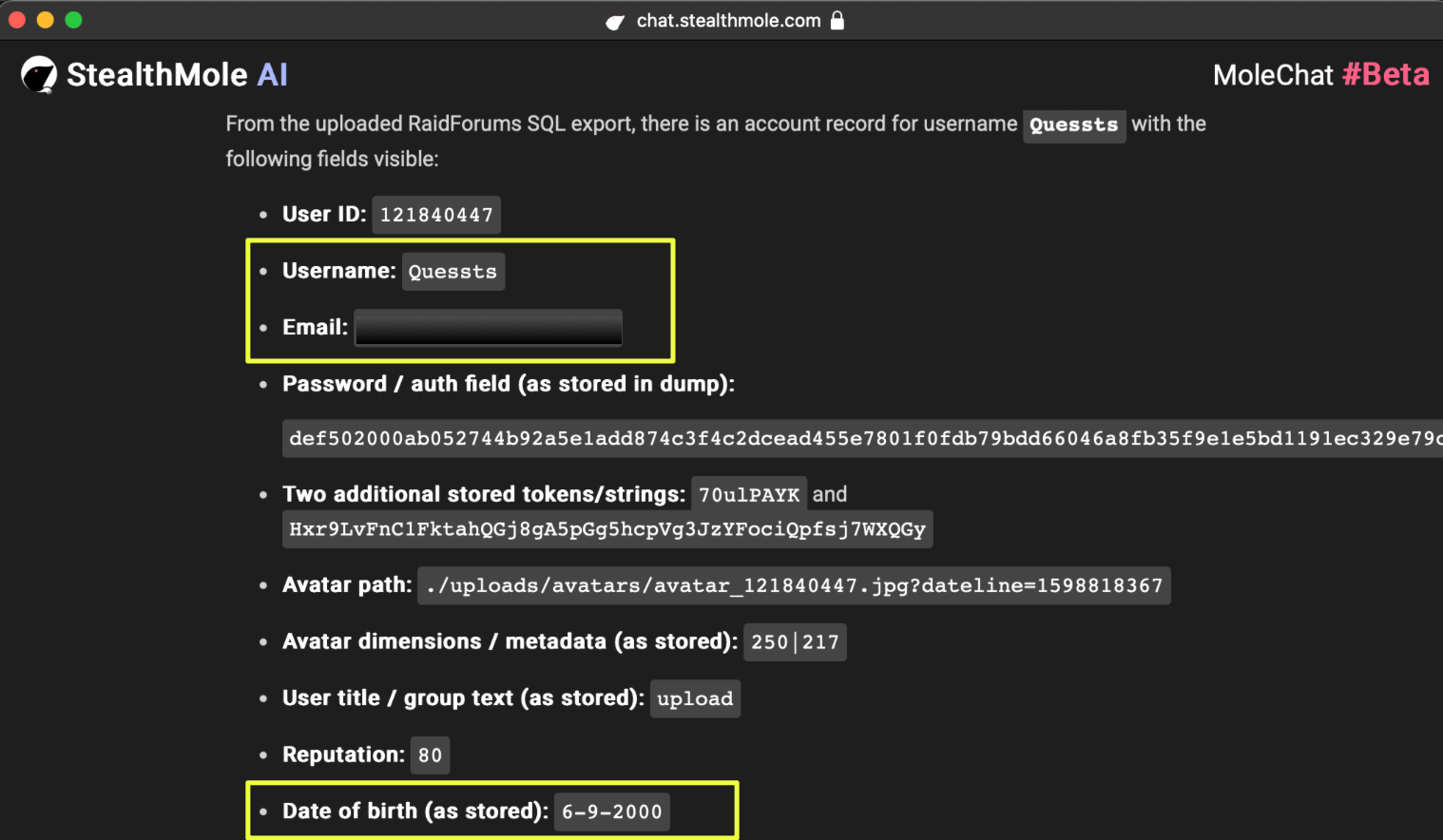

Further examination of the NightSpire ecosystem revealed additional insight into how the group presents itself and attempts to structure its operations. Within the blog infrastructure previously identified, the About page provides a detailed narrative describing the group as an organized collective of cybersecurity specialists rather than a conventional ransomware gang.

The page characterizes NightSpire as an “elite red team collective”, claiming expertise in advanced penetration testing, vulnerability discovery, and network infiltration. According to the site, the group consists of a coordinated team of specialists responsible for different aspects of cyber operations.

|

The page listed several individuals described as members of the group’s team, each associated with a specific role:

- Phantom – Lead Infiltrator

- Reaper – Exploit Developer

- Volt – Network Breach Specialist

- Blaze – Red Team Commander

- Shadow – Malware Engineer

- Blade – Web Application Hacker

The page also includes numerical claims regarding the group’s activities, referencing dozens of compromised systems and vulnerabilities discovered during their operations.

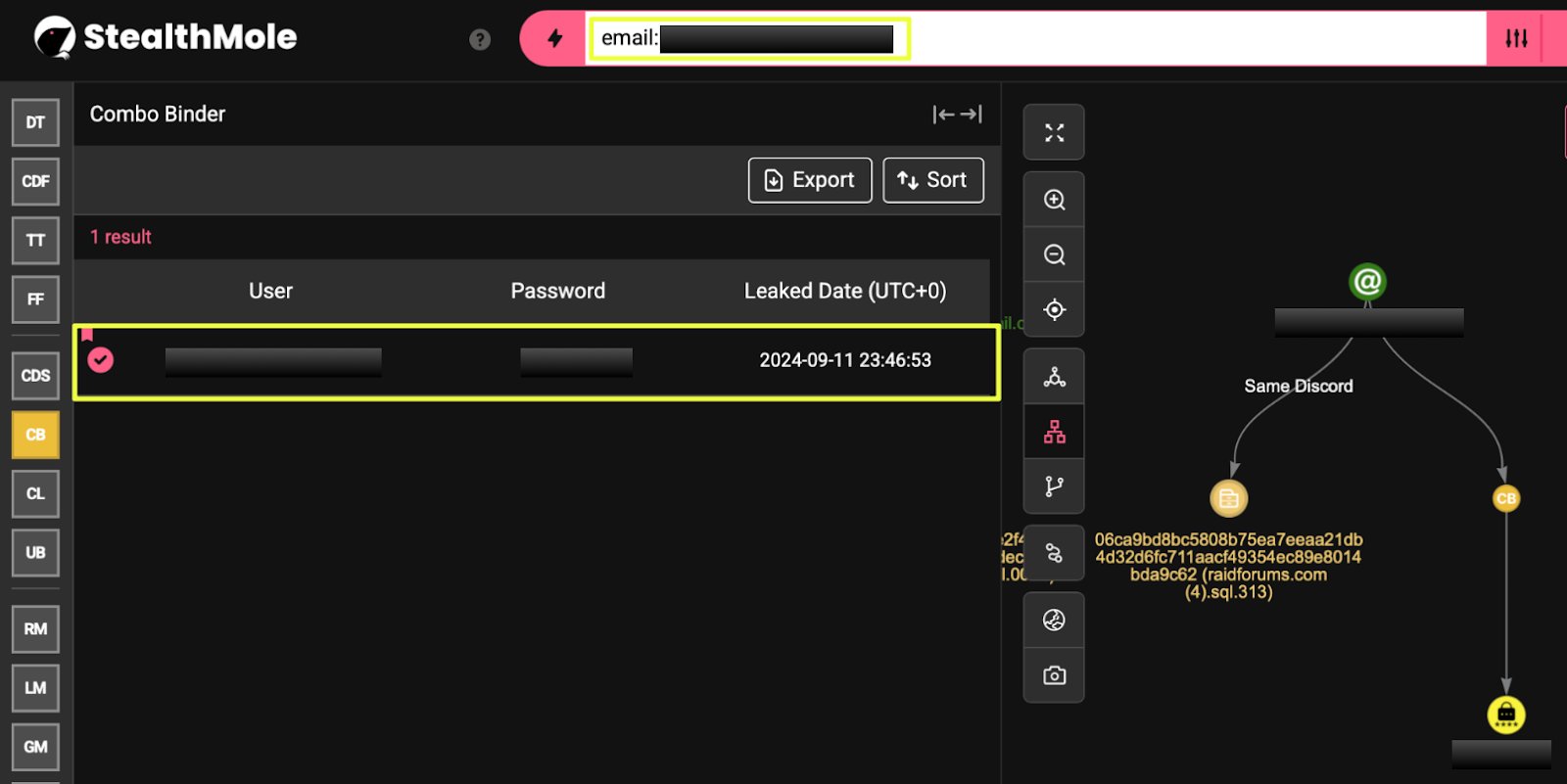

Alongside this organizational narrative, the NightSpire platform also contains clear indicators that the group is attempting to expand its operations through an affiliate-based model. A dedicated affiliate recruitment interface encourages external actors to collaborate with the group, effectively turning NightSpire’s infrastructure into a platform that others can use to conduct attacks. Access to the affiliate portal is gated behind a CAPTCHA verification step, suggesting that the operators are attempting to restrict automated scanning while allowing prospective partners to initiate contact.

|

Messaging associated with the recruitment process emphasizes opportunities for participants to join NightSpire’s campaigns and leverage the group’s infrastructure and tooling. This approach aligns with a Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) model, in which the core operators maintain the underlying ransomware infrastructure while independent affiliates carry out intrusions and deploy the ransomware in exchange for a share of the profits.

Overall, the About page and affiliate recruitment mechanisms present a carefully constructed public image of the operation. On one level, NightSpire attempts to portray itself as a technically skilled red-team collective engaged in advanced cybersecurity activities. At the same time, the group actively maintains ransomware leak sites, negotiation portals, and recruitment channels intended to support extortion campaigns.

|

This contrast highlights how some ransomware groups attempt to frame their activities in terms that resemble legitimate security work, even while operating infrastructure designed to facilitate data theft and ransom negotiations.

Conclusion

This investigation began with a review of Bangladesh’s cyber threat landscape and eventually narrowed to a ransomware operation linked to the NightSpire group. The appearance of a Bangladesh-based textile company on the group’s leak platform served as the initial trigger that led to a deeper examination of the infrastructure and operational elements behind the campaign.

The analysis revealed that NightSpire maintains a structured ecosystem consisting of multiple onion domains, encrypted communication channels, cloud-hosted resources, and an affiliate recruitment mechanism, suggesting an operation designed to scale through external collaborators.

One of the most significant artifacts uncovered during the investigation was the set of malware hashes associated with the group’s infrastructure. Unlike domains, communication channels, or branding, which threat actors frequently rotate, abandon, or rebrand, malware hashes provide a far more persistent technical fingerprint. Even if NightSpire were to modify its public identity, migrate its infrastructure, or reappear under a different name, these hashes could still serve as durable indicators linking future activity back to the same operational tooling or malware family.

Viewed in the broader context of Bangladesh’s evolving cyber threat environment, the NightSpire case illustrates how international ransomware operations intersect with emerging digital ecosystems. As organizations continue to expand their online presence, maintaining visibility into both threat actors and the technical artifacts they leave behind will remain essential for understanding and responding to future campaigns.

Editorial Note

Attribution and capability assessment in cyber investigations are rarely absolute. Online identities can be replicated, exaggerated, or strategically framed for visibility. This case demonstrates how fragmented signals can be methodically assembled to identify patterns without overextending conclusions using StealthMole.

To access the unmasked report or full details, please reach out to us separately.

Contact us: support@stealthmole.com

Labels: Featured, Target Country

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)